Toward a More Equal America, Part 6

In Part 4, I alluded to the fact that “there is emotional work to do here as well,” in the context of creating a more equitable economy. In the final three parts of this series, I want to dig deeper into what that emotional work entails, and at the same time examine why the emotional work that we are doing doesn’t seem to be addressing our overarching neoliberal economic inequality in a meaningful way.

That means that it’s time to take a hard look at social justice – the ideology that seeks to overcome identity-based oppression and that has become firmly entrenched on the leftward end of the American political spectrum. Admittedly this puts me in an awkward position; as a white, cisgender, heterosexual man, social justice etiquette would dictate that I ought to shut up and listen, and most certainly not criticize the overall framework in any way.

So, I offer a critique of mainstream social justice not in my own words, but in the words of three others. Cedric Johnson, a Black man, is an associate professor of political science and African-American Studies at the University of Illinois, Chicago. Adolph Reed, also a Black man, is a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania. Kai Cheng Thom, a transgender woman of Asian descent, is an author, speaker, and cultural worker based in Quebec.

Reed expresses the problem succinctly:

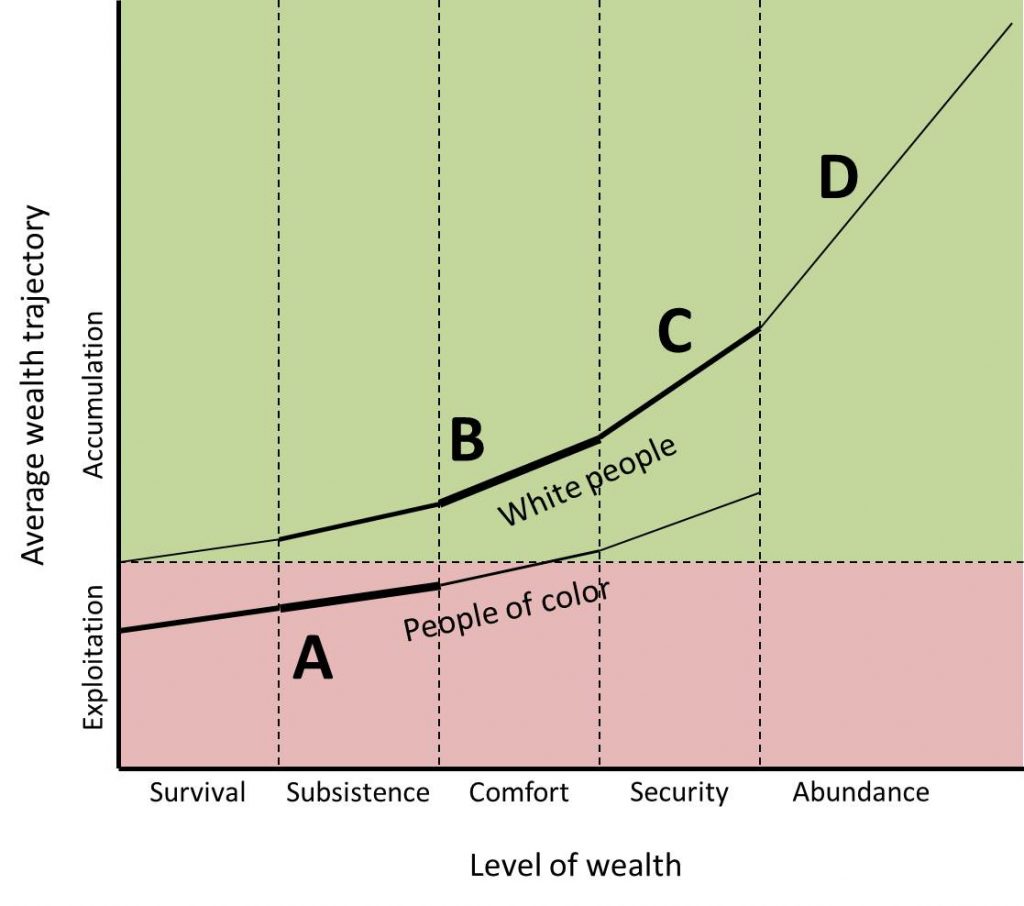

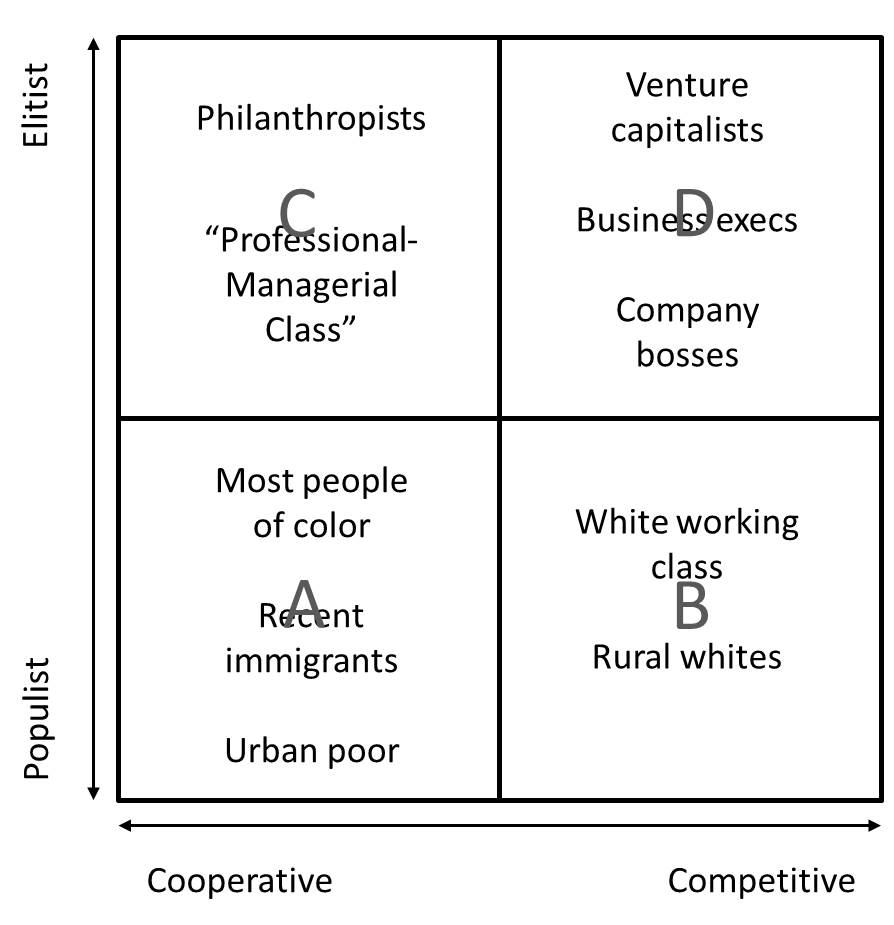

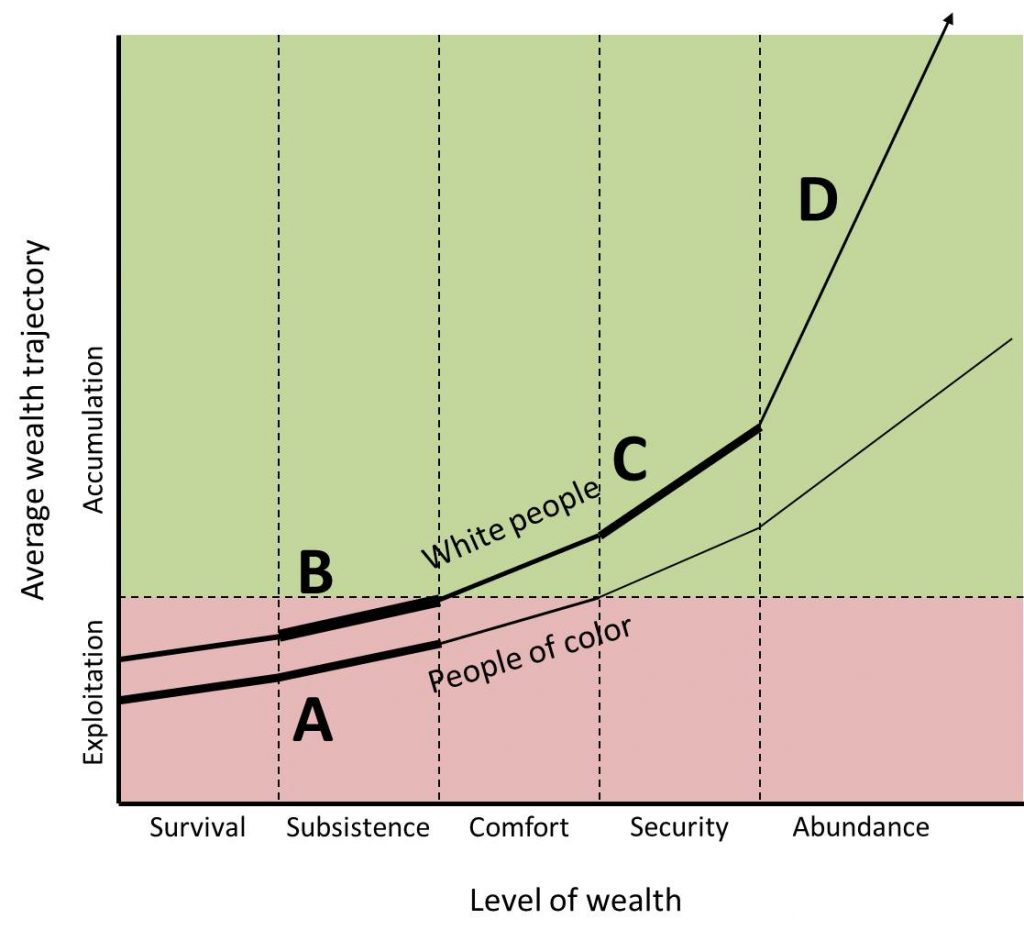

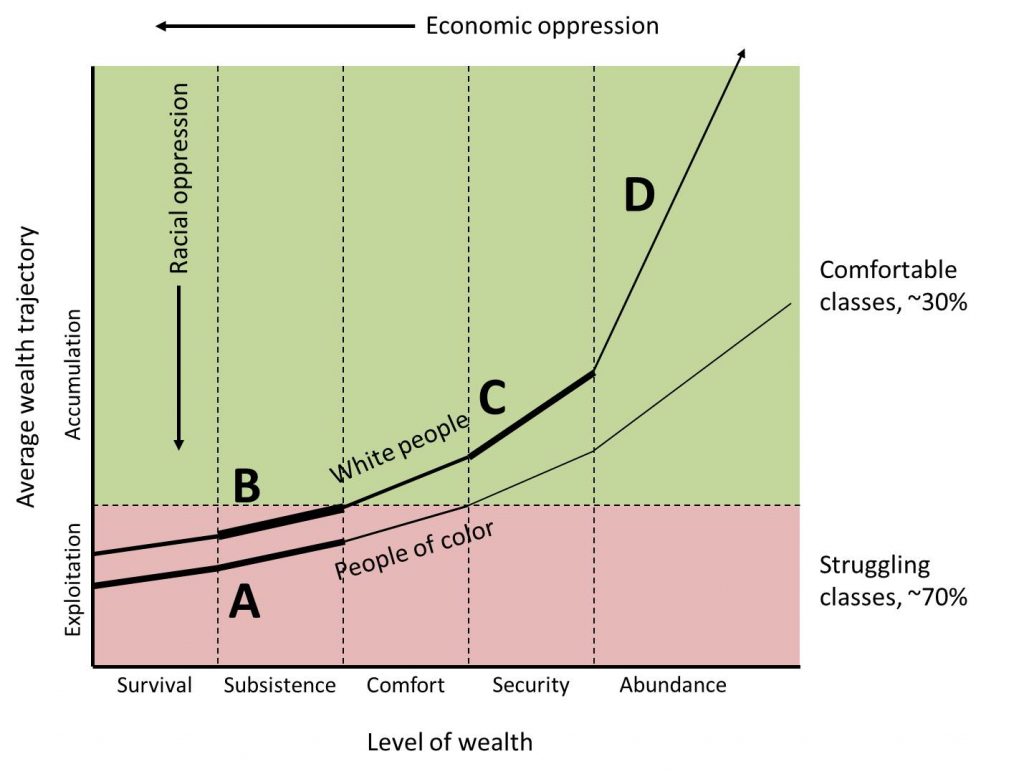

(A)lthough it often comes with a garnish of disparaging but empty references to neoliberalism as a generic sign of bad things, antiracist politics is in fact the left wing of neoliberalism in that its sole metric of social justice is opposition to disparity in the distribution of goods and bads in the society, an ideal that naturalizes the outcomes of capitalist market forces so long as they are equitable along racial (and other identitarian) lines. As I and my colleague Walter Benn Michaels have insisted repeatedly over the last decade, the burden of that ideal of social justice is that the society would be fair if 1% of the population controlled 90% of the resources so long as the dominant 1% were 13% black, 17% Latino, 50% female… etc.”

…

(T)he focus on racial disparity accepts the premise of neoliberal social justice that the problem of inequality is not its magnitude or intensity in general but whether or not it is distributed in a racially equitable way. To the extent that that is the animating principle of a left politics, it is a politics that lies entirely within neoliberalism’s logic.

https://nonsite.org/editorial/how-racial-disparity-does-not-help-make-sense-of-patterns-of-police-violence

Johnson expands on this line of reasoning, critiquing the prioritization of emotional antiracist work over concrete policy changes that would necessarily challenge both economic and racial privilege.

Whiteness studies has produced a form of anti-racist politics focused on public therapy rather than public policy, a politics that actually detracts from building social bonds and solidarity in the context of actual organizing campaigns, everyday life, and purposive political action.

…

The interpretive problems and faulty political assumptions of whiteness studies have become entrenched through the emergence of a therapeutic industry dedicated to rehabilitating interpersonal racism and addressing white privilege through acts of contrition, and have grown more dangerous as they have been amplified and degraded via social media. There is not much evidence that the expansion of this mode of anti-racist trainings over the last few decades has produced a different politics, a willingness to take risk, to sacrifice one’s privileged position to make substantive changes in society, or even altered day-to-day behavior.…

If anything, whiteness deprogramming provides a ready means of egress, a way to demonstrate sympathy without making more difficult, sustained political commitments that might entail contesting institutionalized power. Neither does it require shedding or sharing the actual trappings of middle class privilege, i.e. better salaries, savings and assets, high performing schools, the capacity to travel, social networks, etc., which are codified in popular speech as white privilege, even though these same goods may be shared by other middle class and wealthy ethnics. Whiteness training encourages sharing one’s origin story, failings and sense of torment, but beyond charitable giving, it does not necessitate sharing resources at the level of redistributive public policy, i.e. through expansion of the universal social wage, commuter taxes, consolidation of urban-suburban school districts, revenue sharing across metropolitan divides, federally-managed public works projects etc.

There is also a millenarian and liberal individualist dimension to the kind of anti-racist politics embodied in whiteness studies, notions of white privilege and the like. We are told individuals must correct their flaws before they can participate with others, a view that runs counter to what should be conventional wisdom about human behavior and social movement dynamics. The assumption that the therapeutic work needs to happen first is simply wrong, and there are plenty of examples throughout history and in our own times where we can find imperfect people working to realize and advance their common concerns.

The work of building solidarity lies elsewhere, not in therapy aimed at self-actualization, but in lived social relations and sustained political work that transforms participants’ social consciousness and collective sense of historical possibility. Those everyday social relations and the context of political work are always defined by the presence of differences, whether those are differences of background, perspective, maturity, knowledge, insight, power, capacity, and passions, and none of these are calibrated strictly in concert with racial, ethnic, gender or other corporeal identities.

…

We should be able to talk about situated-class experiences, i.e., ascriptive gender and racial hierarchies, sectoral and regional variations in working lives, unique occupational subcultures, idiosyncratic worker concerns and daily issues, without losing sight of the fundamental capitalist class relation of exploitation, and the dependency on wage labor endured by the vast majority of the U.S. population. Moreover, when we discuss what are often treated as discrete identity-based issues, i.e. matters of hyperpolicing, health disparities, urban unemployment, environmental racism, the gender gap in wages, affordable housing crises and gentrification, we should be clear that those problems originate from the tremendous power capital wields over all of our lives, and contesting that power is essential to addressing those specific concerns and creating a more just state of affairs.

Excerpts from https://nonsite.org/article/the-wages-of-roediger-why-three-decades-of-whiteness-studies-has-not-produced-the-left-we-need

One effect of this is that we collect data on racial, ethnic, gender, and other identity-based discrepancies across a wide array of areas of concern: wages, hiring, college admissions, proportion of various workforces, deaths in police custody, deaths from various causes, and just about every aspect of society where data are collected. By pre-defining these identities to be the variables of interest, we can fail to properly determine causality when many other variables may be involved.

For example, we know that Black women experience pregnancy-related mortality at a rate three times that of white women. We can hypothesize that it is due to the stress of experiencing racism and underlying health conditions exacerbated by racism, but without further information as to the cause it is difficult to know where to focus activism. If it is due to direct experiences of racism, then antiracism training may be the answer, but if it is due to – say – poverty and lack of health insurance, then it would be better to focus on lifting these women – and all impoverished women – out of poverty and providing universal health care.

We can determine, in this example, that women in “poor” counties (>15% poverty) are twice as likely to experience pregnancy-related mortality than women in “rich” counties (<5% poverty), but all counties have a wide range of income levels and we don’t actually collect income data on an individual basis to assess whether poverty might be a more explanatory factor than race.

In the wake of the recent Black Lives Matter protests following the police murder of George Floyd, Johnson penned a critique that I highly recommend reading: The Triumph of Black Lives Matter and Neoliberal Redemption. In it, he notes that large corporations that were facing intense scrutiny and condemnation for their labor practices during the Covid-19 pandemic received a public relations windfall from their support of the Black Lives Matter protests. I quote some excerpts below.

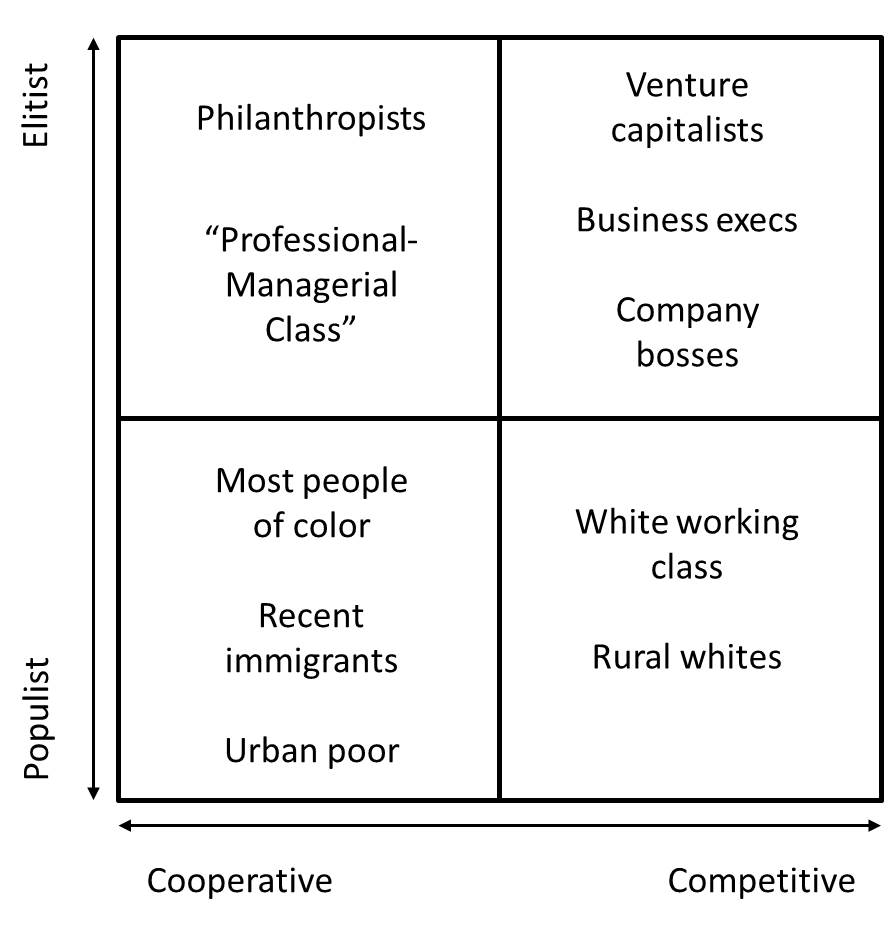

Nearly all of the Democrat leadership who “took a knee” against racist policing, have openly opposed Medicare for All, free higher education, and the expansion of other public goods, but their technical reforms to reduce excessive force incidents and prosecute police for misconduct are the perfect way of displaying commitment to racial justice, while perpetuating the very pro-market logics and class relations that stress policing and mass incarceration were invented to protect.

…

Black Lives Matter sentiment is essentially a militant expression of racial liberalism. Such expressions are not a threat but rather a bulwark to the neoliberal project that has obliterated the social wage, gutted public sector employment and worker pensions, undermined collective bargaining and union power, and rolled out an expansive carceral apparatus, all developments that have adversely affected black workers and communities. Sure, some activists are calling for defunding police departments and de-carceration, but as a popular slogan, Black Lives Matter is a cry for full recognition within the established terms of liberal democratic capitalism. And the ruling class agrees.

During the so-called Black Out Tuesday social media event, corporate giants like Walmart and Amazon widely condemned the killing of George Floyd and other policing excesses. Gestural anti-racism was already evident at Amazon, which flew the red, black and green black liberation flag over its Seattle headquarters this past February. The world’s wealthiest man, Jeff Bezos even took the time to respond personally to customer upset that Amazon expressed sympathy with the George Floyd protestors. “‘Black lives matter’ doesn’t mean other lives don’t matter,” the Amazon CEO wrote, “I have a 20-year-old son, and I simply don’t worry that he might be choked to death while being detained one day. It’s not something I worry about. Black parents can’t say the same.” Bezos also pledged $10 million in support of “social justice organizations”…..

The leadership of Warner, Sony Music and Walmart each committed $100 million to similar organizations. The protests have provided a public relations windfall for Bezos and his ilk. Only weeks before George Floyd’s killing, Amazon, Instacart, GrubHub and other delivery-based firms, which became crucial for commodity circulation during the national shelter-in-place, faced mounting pressure from labor activists over their inadequate protections, low wages, lack of health benefits and other working conditions. Corporate anti-racism is the perfect egress from these labor conflicts. Black lives matter to the front office, as long as they don’t demand a living wage, personal protective equipment and quality health care.

Excerpts from https://nonsite.org/editorial/the-triumph-of-black-lives-matter-and-neoliberal-redemption

From the perspective of transgender equality, Kai Cheng Thom writes, in Trans Visibility Does Not Equal Trans Liberation:

Our revolutionary fire burns bright as always, but I am afraid that it is being misdirected, co-opted. Neoliberalism, the deadly, advanced stage of the capitalist system in which we live, is stealing trans liberation.

Instead of being able to gain access to resources, we are given representation in mainstream media – a perk that helps us enjoy television and movies while continuing to suffer homelessness and joblessness. Instead of being granted freedom, we are being sold a product: an illusion of “equality” that is ultimately empty.

To achieve trans liberation, we must turn our gaze to ending neoliberalism.

…

Neoliberalism erodes human-rights movements in an insidious way. It co-opts the thinking and operations of human-rights activism by creating fear and scarcity, so that our political goals are forced to focus not on envisioning a better future for all but on personal survival. Hoarding resources, assimilation into the status quo, and no-holds-barred individualism are second nature to neoliberal thinking.

…

In my practice as a social worker, I see more and more wealthy, usually white, middle-class youth and children coming out as trans. It’s beautiful. They are brave and resilient; and sometimes, their families actually support them in transitioning and advocating for their access to school, healthcare, university.

Yet I see just as many trans youth, mostly of color, who are estranged from their families, living in shelters, blocked from accessing the resources they need for day-to-day living, let alone medical transition and higher education.

Trans visibility is brighter than ever, trans rights awareness is at an all-time high. Yet the class divide between trans people grows and grows.

…

The myth of exceptionalism has always been a cornerstone of neoliberal philosophy – this is the idea that since a few people can “make it” under capitalism, then everyone else can do the same. It is a myth that conflates the success of an individual with the prosperity of their entire class, and it is used to hide the barriers of systemic discrimination and violence.

https://www.them.us/story/trans-visibility-does-not-equal-trans-liberation

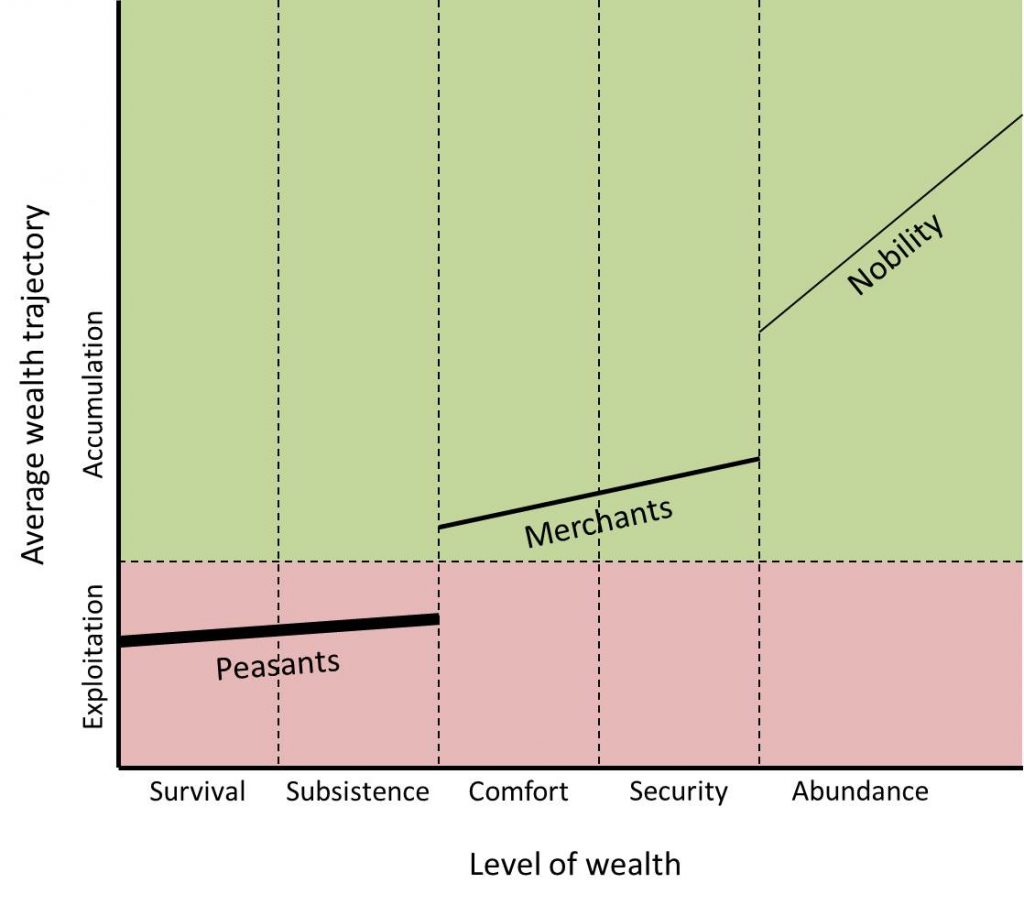

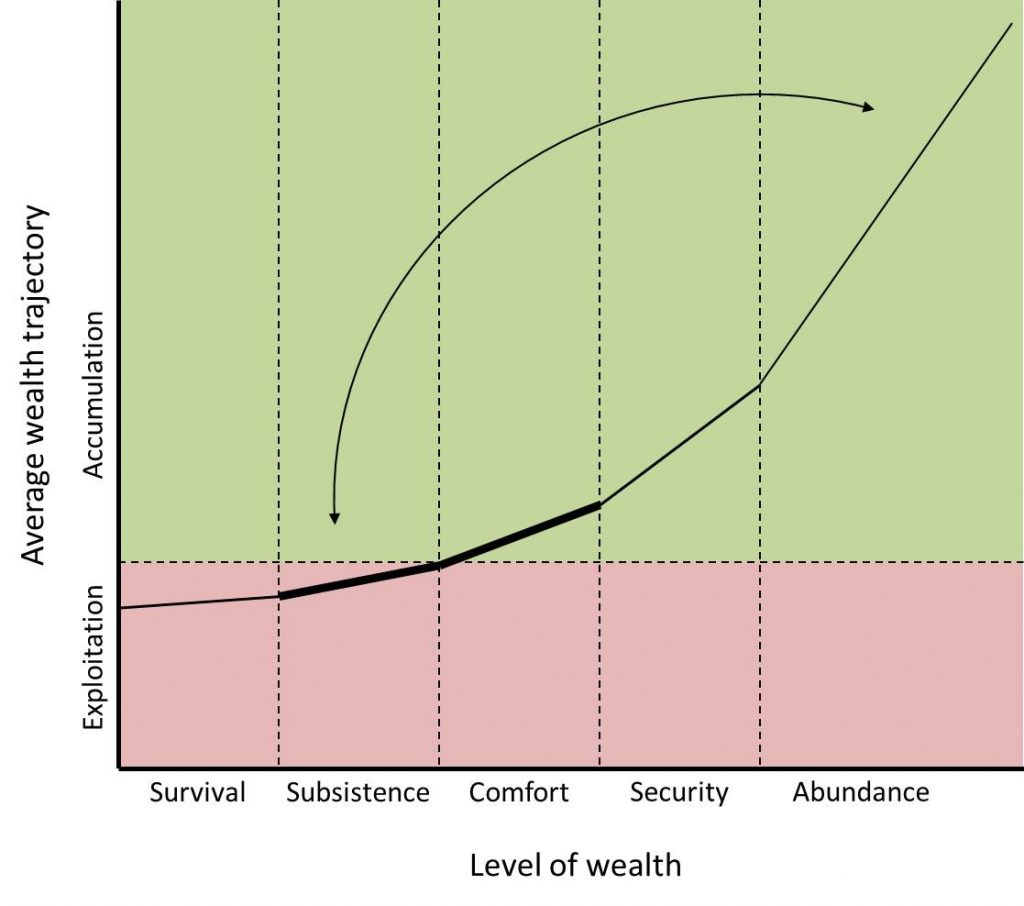

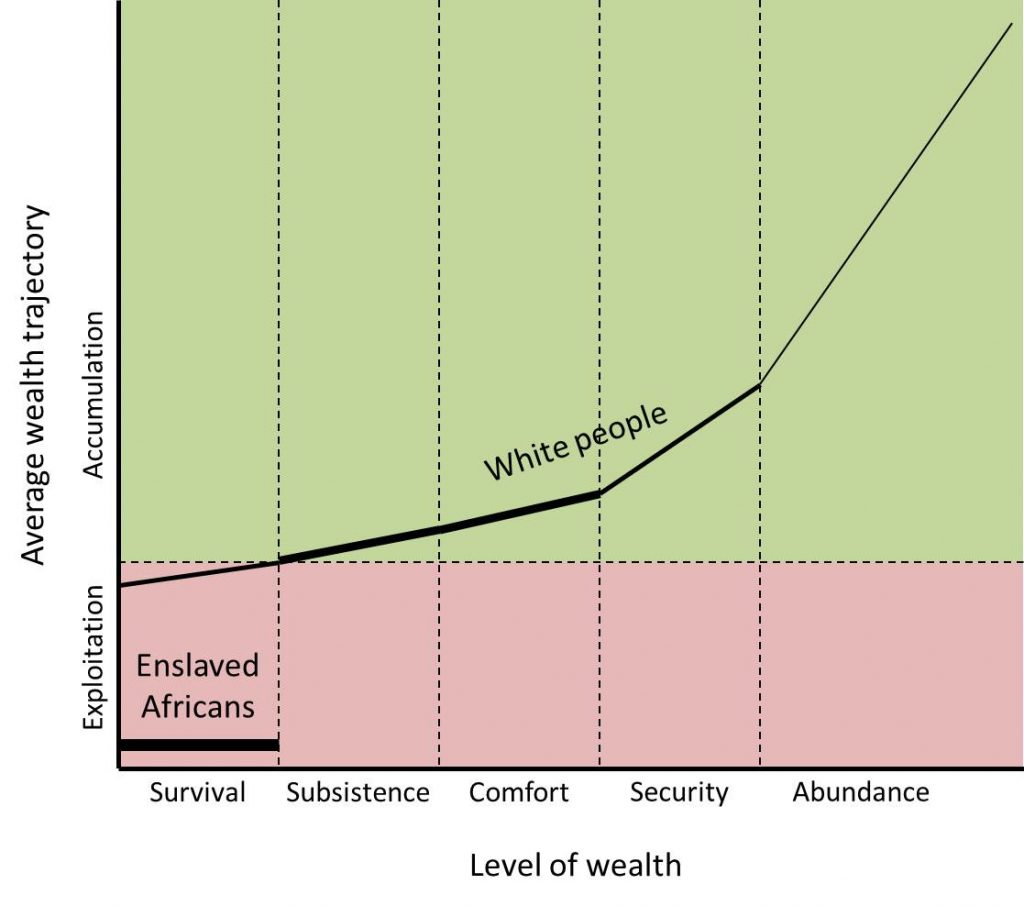

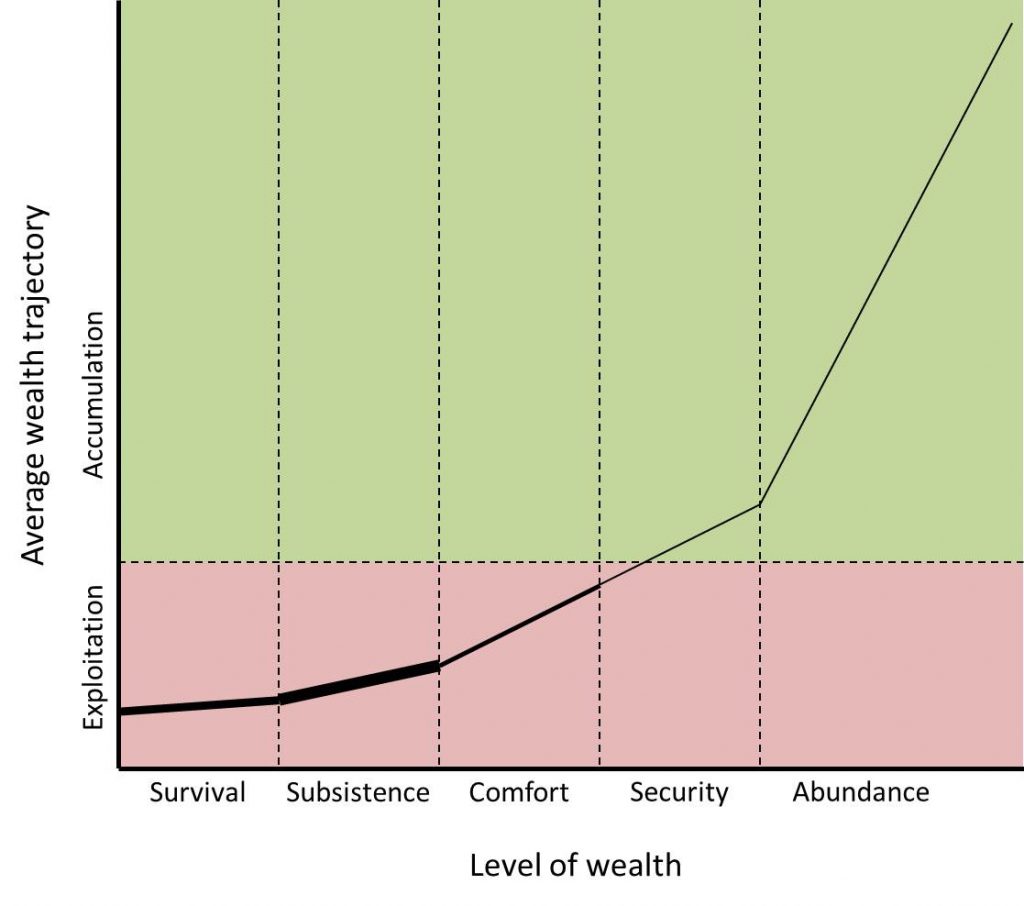

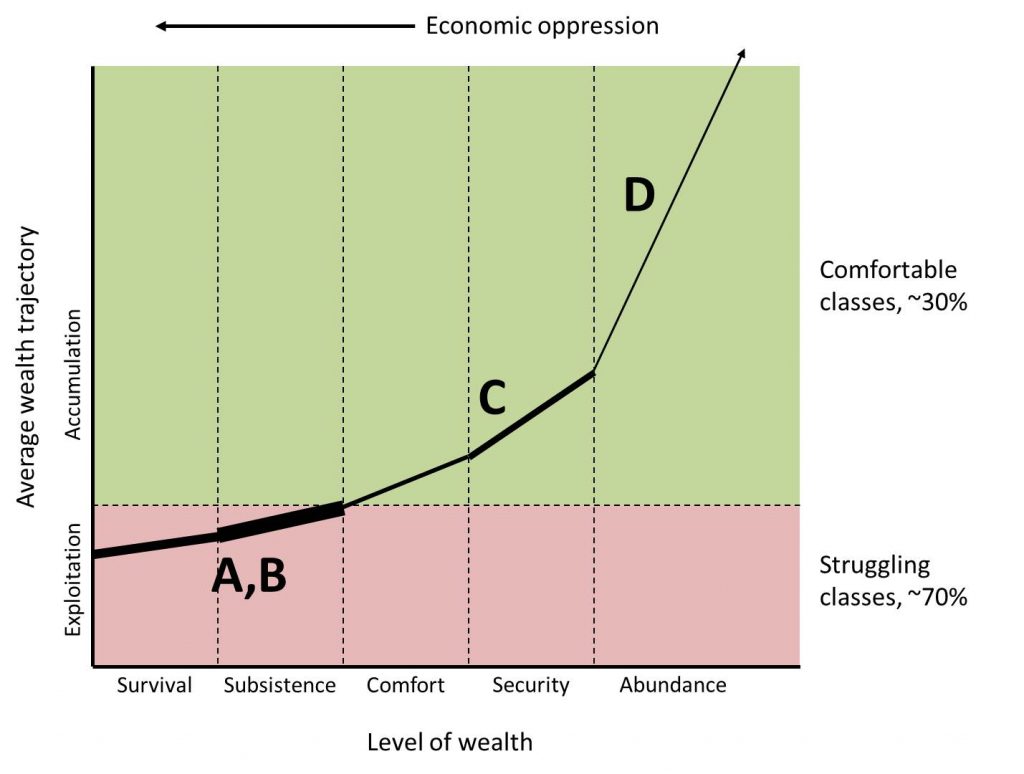

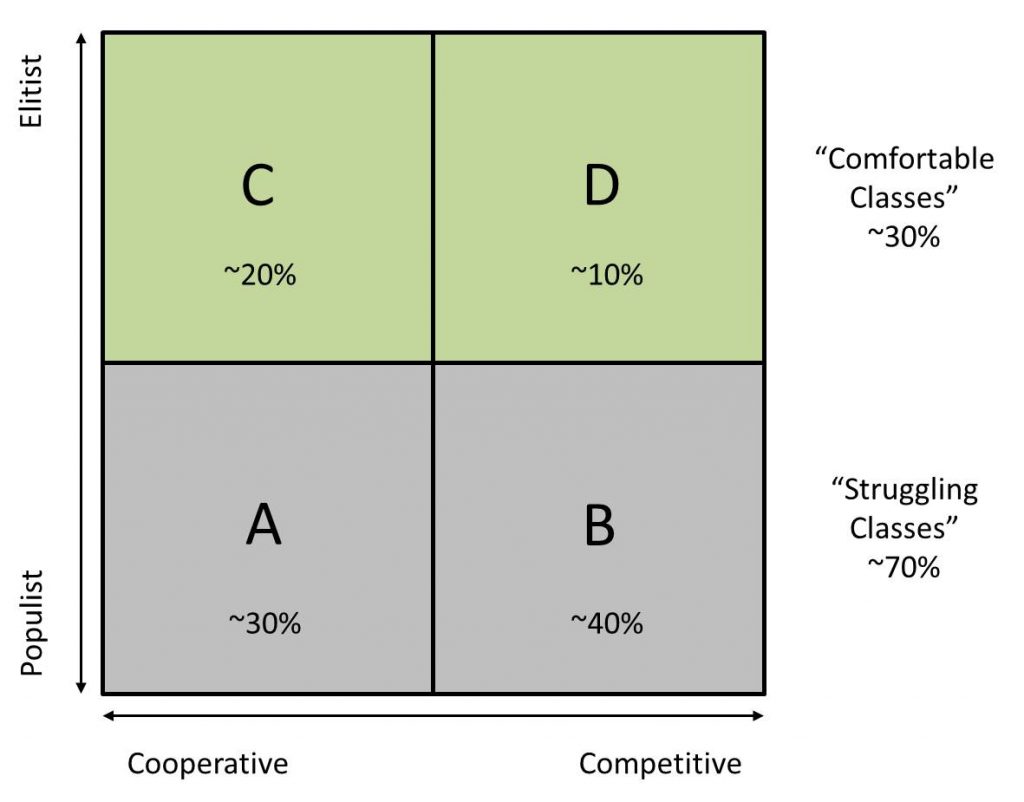

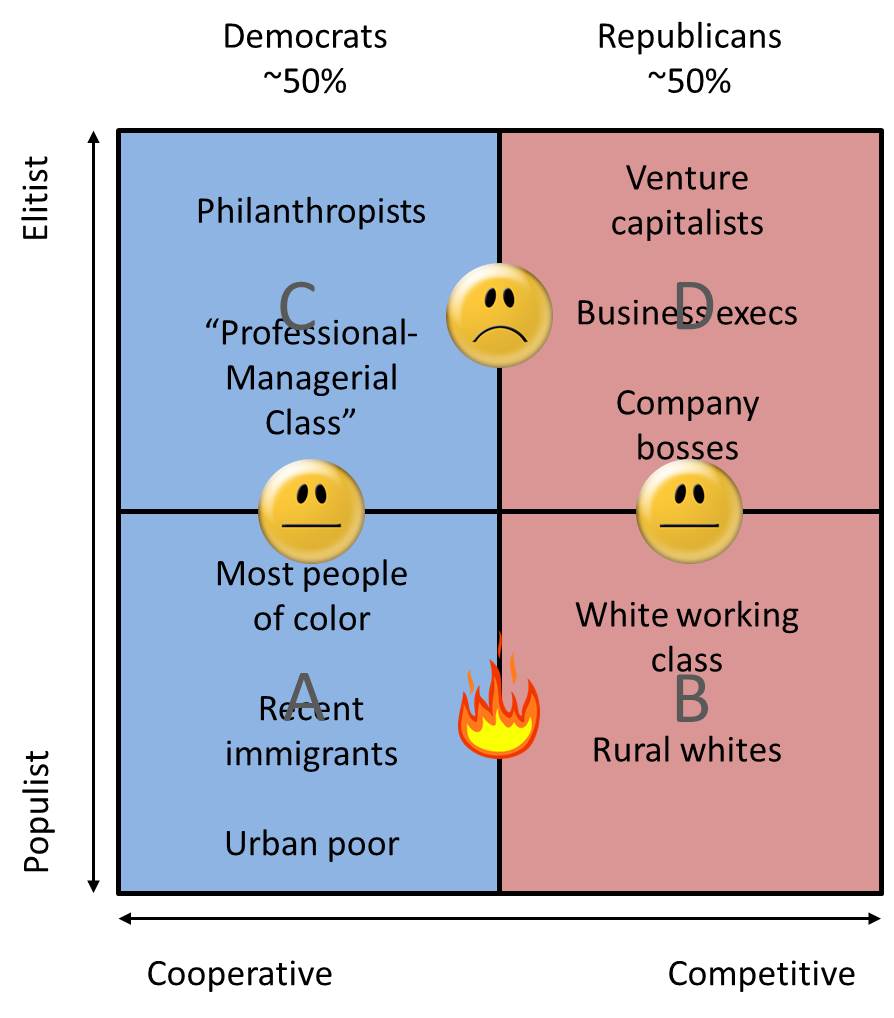

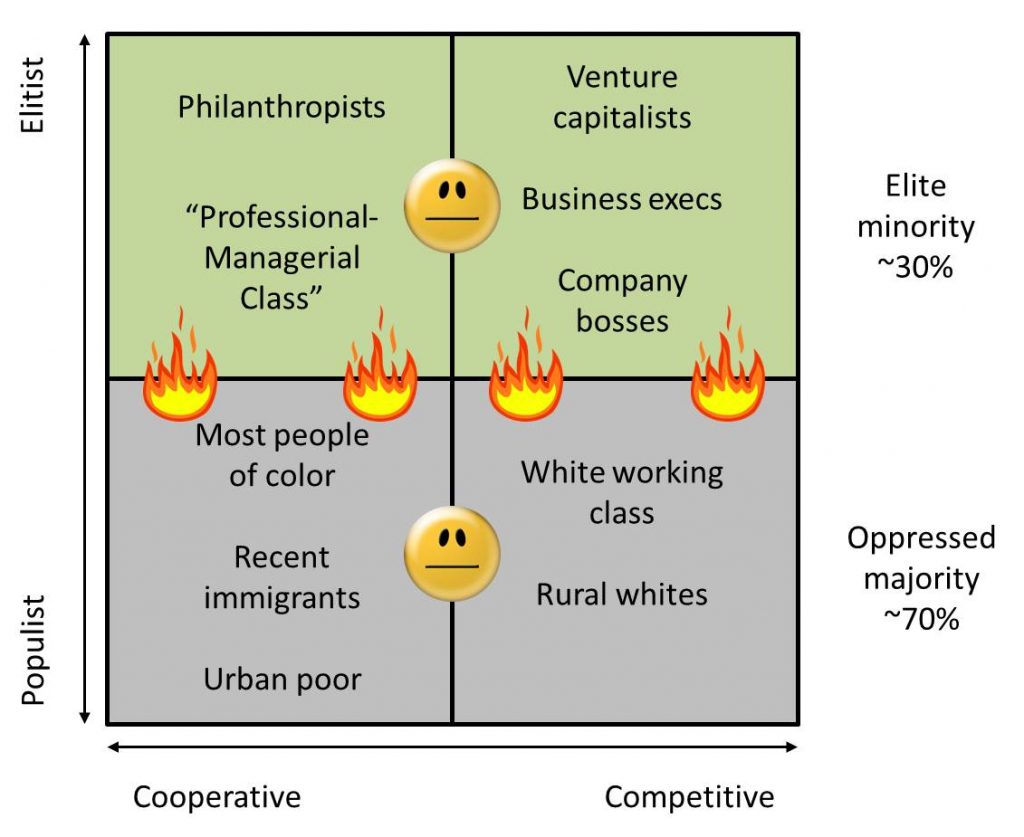

If we view the American Casino (Part 2) as a rigged card game played with predetermined good hands and bad hands, then the strategy of neoliberal social justice is equivalent to handing out aces to people with marginalized identities. For those whose hands are already good, the ace can make a difference. For those whose hands offer no chance of winning, adding an ace usually doesn’t help. The deeply unethical rules of the game remain unquestioned.

Thom closes with an impassioned plea for a society in which trans people don’t just have representation among the elite, but freedom to thrive:

I am not the first trans person to make these arguments, and I will be far from the last. As a diasporic trans woman of color, I come from a history of brilliant thinkers and fierce activism.

As a generation of young trans people like myself with access to education and a public platform emerges, we will each have to ask ourselves the question: What battles will we choose to fight, and for whom? Will those of us with the greatest chance of succeeding as a part of the neoliberal status quo fight for our piece of the pie alone, or will we try to overturn the table of capitalism and white supremacy, as our revolutionary foreparents did before us?

I know that I don’t want to live in a world where trans people can access medical transition care only if they have the insurance to pay for it. I want everyone to get the healthcare they need.

I don’t want to live in a world where middle class trans people can use public washrooms, but homeless trans people are barred from public spaces. I want to live in a world where everyone has a home.

I don’t want to live in a world where trans people can join the military or the police and join in the violent oppression of people of color around the world. I want to live in a world without wars or police brutality.

I don’t want to live in a world where trans people are put in prisons that match their gender identity. I want to live in a world without prisons.

I don’t want to live in a world where a handful of trans celebrities make millions of dollars while the rest of us struggle to survive. I want to live in a world where we all have what we need to thrive.

I don’t want to live in a world where some trans people are considered normal and others are considered freaks. I want to live in a world where all of our freakish, ugly, gorgeous magnificence is celebrated for its honesty, glory, and possibility.

My dear trans kindred – weird sisters, brothers grim and gay, siblings-in-arms: What kind of world do you want to live in?

https://www.them.us/story/trans-visibility-does-not-equal-trans-liberation