Where are we now?

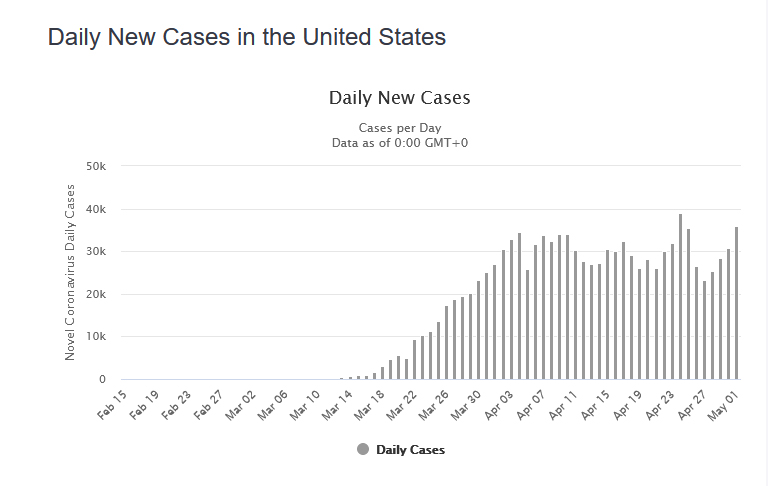

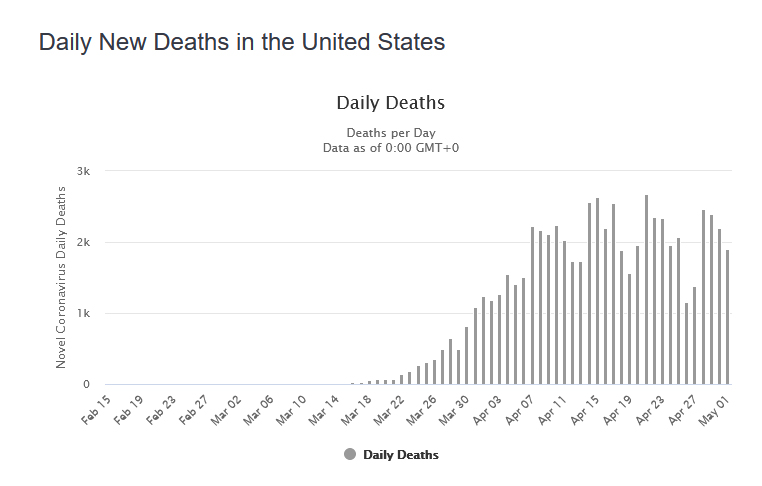

It’s been two weeks since my last COVID-19 post, when I predicted that case counts and deaths would begin a noticeable decline as they have across most of Europe. Instead, we have seen a stubborn plateau. Testing continues to increase, so it is likely that actual new cases are declining slowly, but daily deaths continue to average around 2000 per day, which means that ~25% more people are dying in the United States than in normal times.

The picture is different state by state. New York City, where an estimated 20% of the population was infected, is following an Italian trend, with a steady decrease in death and infection now down at least 50% from last month’s peak. Some areas, including Minnesota and Washington DC, are still seeing an increase despite lockdown measures. Still others, including Oregon, Montana, and Hawaii, are seeing cases and deaths slowly decline despite never experiencing widespread infection.

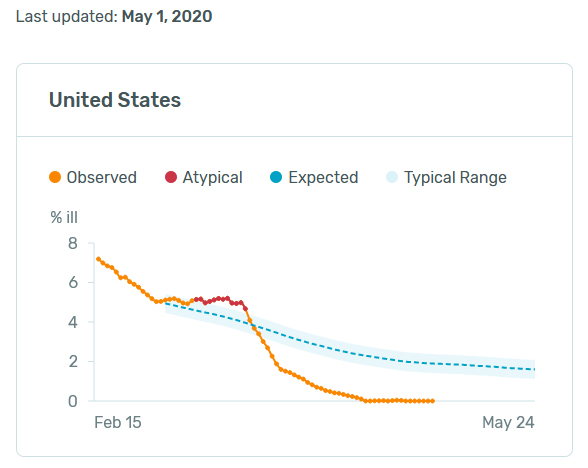

Nationwide, smart thermometer users continue to report zero fevers, suggesting that the disease is now primarily confined to unrepresented populations: lower-class essential workers and care home residents being the most-affected demographics in this moment.

Despite continued high case counts, most US states are either beginning to relax restrictions or making plans to begin the process in the next few weeks. We can hope that increased testing and contact tracing will allow us to keep infection levels from rising, but there is also a growing consensus that we can’t keep parts of our society shuttered indefinitely, and that if we can’t ultimately contain this virus we may need to adapt to it, perhaps following a Swedish model.

Seeking perspective

Most of us have been thoroughly confused, and seriously frightened, by the graphs, stories, and comparisons presented in the media throughout this crisis. In particular, we have been inundated with inappropriate comparisons and selective individual accounts.

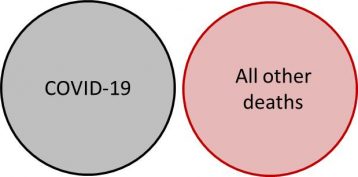

Most of these comparisons are based on the unquestioned assumption that the severity of a crisis is directly proportional to the body count. So it is that COVID-19 rapidly became worse than 9/11 (3,000 killed) and is now worse than the Vietnam War (58,000 killed). But it doesn’t actually work that way. We cannot reasonably compare accidents, mass murder, war, and disease. As an exercise, consider the relative national emotional impact of the Challenger space shuttle explosion (7 deaths), 9/11 (3000 deaths), the 2017-18 flu season (80,000 deaths), and the annual cancer death toll (600,000 deaths). Since 9/11, nearly 4,000 people have died of cancer for every person that died when the twin towers collapsed, but no one would dare to suggest that cancer is 4,000 times worse than the attack.

Of the roughly two million people that die every year in the United States, the majority die of some sort of disease: heart disease, cancer, high blood pressure/stroke, influenza, etc. This is the appropriate context in which to assess the impact of a pandemic. Of those two million people, many of them experience substantial pain and suffering, and many of those deaths were not strictly unavoidable, instead being caused or accelerated by poverty, addiction, loneliness, diet, environmental toxins, and a host of other factors. When we hear harrowing accounts of people suffering from COVID-19, we can forget that there are far greater numbers of untold harrowing accounts in our homes and hospitals: metastatic cancer, autoimmune disease, liver failure, lung disease, and the list goes on.

Furthermore, COVID-19 deaths match the age breakdown of typical deaths quite closely. It’s not exactly true that this illness specifically targets the elderly and spares the young, in the manner of heart disease or dementia. Rather, if we were to compare the ages of COVID-19 deaths to a random sample of obituary pages from past years, we would find that the age breakdown is almost identical: roughly half over age 80, most over age 60, and very few under age 40. The only difference would be the near complete absence of children and teens from the COVID-19 column. So unlike the 1918 flu pandemic, which seemed to target those in the 20-40 age range by stimulating a self-destructive immune response, COVID-19 is following the standard mortality tables with regard to age-based impact.

A 100-year bug

Most of us are familiar with the concept of a 100-year flood: a flood of a magnitude that recurs on average once per century. The same understanding can be applied to pandemics.

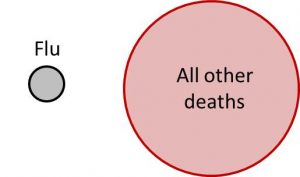

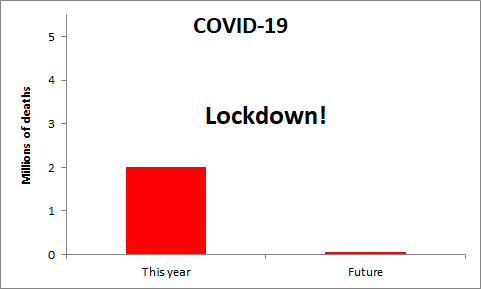

A 10-year bug would be roughly equivalent to the 2017-18 flu season in the US, causing around 80,000 deaths. It is possible, but increasingly unlikely, that we will confine COVID-19 to this level. Visually, this is what a 10-year bug looks like:

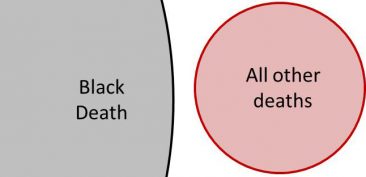

The last major pandemic to spread around the world was the “Spanish” flu in 1918-1920. That disease caused 600,000 deaths in the United States. The population of the US has increased slightly more than threefold since that time, so the equivalent number of deaths today would be two million – which also happens to be a good estimate of the number of expected deaths if COVID-19 were allowed to spread freely throughout the population, and it is also the number of people who die in the United States in a typical year. So, if left unmanaged, COVID-19 could become a 100-year bug with a death breakdown like this:

A 100-year bug would condense two years of death into a single year, and our collective chance of surviving another year would be the same as our chance of surviving another two years in normal times. It would be a time of great sorrow, and we would do well to avoid it if we can do so without completely destroying our lives in other ways, but it would hardly be “apocalyptic,” “catastrophic,” or any of the other frightening words flying around the media-sphere.

We can save those words for a 1000-year bug, which with any luck none of us alive today will live to experience. The last widespread example in history would be the Black Death, which killed 50% of the population of Europe from 1348-1350. Such a pandemic could easily happen again, if a virus with the death rate of Ebola were to achieve the contagiousness of COVID-19 (R=3) or measles (R=12). Such a pandemic would look like this, and the world that came after would be truly changed.

Yes, we can act! (but why?)

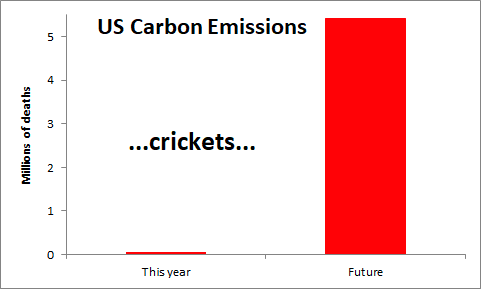

One of the great surprises of the last two months – for me – has been the degree to which COVID-19 has catalyzed previously-unthinkable changes in our society. Facing projections of catastrophic climate change we can’t even pass modest improvements in vehicle fuel economy or stop increasing the amount of carbon we emit each year, but give us a virus that could kill fewer than 1% of us and we will all stay home, save lives, and reduce our air travel by 95%.

If we can understand what exactly about this crisis enabled us to take action, perhaps we can improve our chances of making other much-needed course corrections in the years ahead. To me, the critical elements here are a threat to our notion of progress and a clear near-term danger.

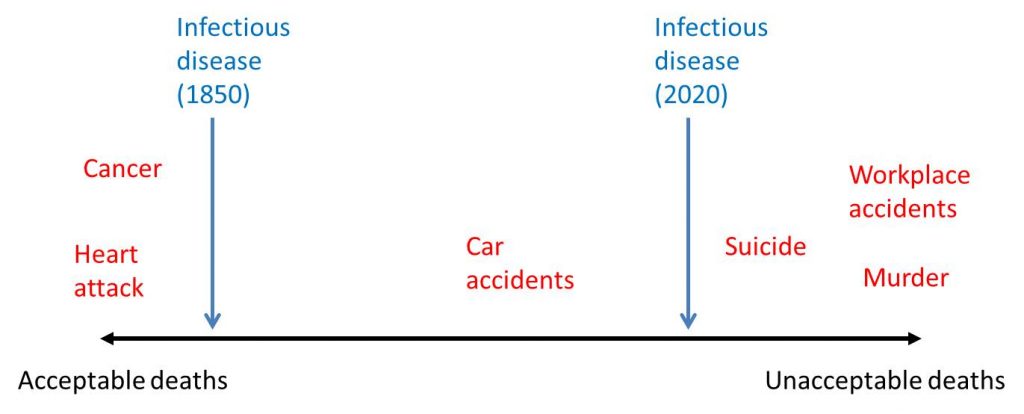

The past 150 years have seen a dramatic reduction in deaths due to infectious disease, thanks to advances in antibiotics, vaccines, and medical technology in general. We have flu and an increasing number of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, but we no longer have smallpox, polio, measles, typhoid, or cholera in the US. This is by all accounts a positive trend, but it has had a psychological side-effect of moving death from infectious disease along the spectrum of societal acceptability. What would once have been viewed as an act of God or nature to be endured has now become a step backwards, a loss of control, to be avoided even at a very high cost. We have come to accept a rising incidence of cancer – better living through chemistry – and even vehicle accidents, but we are no longer so tolerant of pathogenic microbes in our midst.

As our quadrennial elections and investment decisions make clear, we are much more likely to think and act on short time scales. And when it comes to immediacy, it is hard to to beat a virus that could infect us tomorrow and land us in a grave within a month. This crisis makes clear that we are collectively able to change our habits, even sacrifice our economic engine, in response to a relatively modest short term threat. Unfortunately, many of the impending crises that humanity faces – climate change, resource shortages, topsoil loss, air pollution – are objectively worse than even unmitigated COVID-19 but not nearly as acute. One question to ask ourselves, post-pandemic, is how we might reframe longer-term crises in order to spur in-the-moment action.

Shining a light into dark corners

The meat industry

The US meat industry has been all over the news in the past two weeks, as COVID-19 has been spreading rapidly among packing plant workers, and the resulting closures have created a bottleneck forcing farmers to euthanize animals and threatening shortages and price spikes on grocery store shelves. This news coverage is, in turn, giving Americans a better sense of where their meat comes from, and it’s not a pretty picture.

Each year in United States, we consume eight billion chickens, 226 million turkeys, 123 million pigs, and 36 million cattle. Per person, that works out to an annual diet of 24 chickens, 2/3 of a turkey, 1/3 of a pig, and 1/10 of a cow. That actually doesn’t seem too excessive to me, although we could certainly lighten our footprint by consuming less meat. The problems arise from industrialization and commodification of the process, with minimal regard for the animals themselves or for the humans that work in the industry.

Thousands of years ago when humans domesticated animals for meat, milk, and eggs, we made a biological bargain. To the animals, we offered safety from predators, protection from the elements, plentiful food, and abundant opportunities for reproduction. In return we claimed their bodies, or their milk or eggs, for our nourishment. Up until the year 1800 or so it was a relational system, with farmers taking pride in tending their animals well, animals free to explore pastures and have their own experience of the world, and skilled butchers in each town and city transforming those animals into bacon, sausage, hamburger, and steaks for the table.

Then came industrialization and economies of scale, but some processes scale more easily than others. With an equipment upgrade, one miller can expand from grinding a ton of wheat each day to 100 tons a day. One farmer can expand from harvesting five acres of corn to harvesting 500 acres. But animals remain discrete, biological, imperfect, messy. Every chicken must be eviscerated by a human hand, head and feet removed, cut along and between the bones to separate breasts from thighs from wings. Short of advanced robotics, this is nearly impossible to mechanize. So in order to have cheap hot dogs, chicken breasts, and lunchmeat in the supermarket, we employ a vast number of workers – mostly underpaid and underappreciated recent immigrants laboring in cramped and unpleasant conditions – in meat packing plants around the country. And in those cramped, human, blood-spattered quarters, a virus like COVID-19 spreads like wildfire.

These plants have a voracious appetite for animals. The first plant to close, Smithfield in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, is designed to kill 20,000 pigs a day. We may still have bucolic visions of farmyards full of a diverse array of animals – and those farms still exist – but that’s not where those 20,000 pigs come from. Those pigs come from barns holding 2500 hogs apiece in a mucky soup of their own waste and managed for the sole purpose of producing the traded commodity known as pork. The pigs therein have been bred to maximize growth rate and have seen no other sight than the muddy floor and an endless writhing sea of other pigs for their entire short lives. It is the same in the chicken barns, the turkey barns, and the cattle feedlots. In our desire to produce maximum product at minimum price we have neglected to hold up our end of the biological bargain. We seem to have forgotten that such a bargain ever existed, or that indeed we might owe these conscious, neurologically complex beings some ability to experience the world on their own terms, aside from their final destination as our nourishment. This may all seem normal now, but I suspect that some time in the future we will look back on the massive concentrated animal operations of today with the same disgust that we feel when we contemplate our history of human slavery.

There are parallel systems in place that have not forgotten the old ways. While others searched empty shelves for an Easter ham, we pulled one out of the freezer, the last cut remaining from a quarter hog. A friend of ours raises three pigs every year, free to roam in the summer sun, and in return for a quarter of a pig – enough to keep us in pork for half a year – we traded her 50 lbs of onions from our garden, honey from our bees, homebrewed mead, and some of our homegrown quinoa. Every year there are more small farms raising animals the old fashioned way, many of them started by frustrated consumers unwilling to buy factory meat.

This crisis is revealing the primary weakness of industrial, globalized systems: efficiency is the enemy of resiliency. To maximize efficiency we need size, consolidation, just-in-time delivery, and minimal surplus capacity. Disrupt one piece of a gargantuan supply chain, and the whole system falters. To maximize resiliency in the face of the inevitable crises ahead we need diversity, redundancy, and dissemination of production. We need to re-localize our meat production and our food systems in general, to remember our biological bargain, and to restore relationship and connection to a commodified world.

Nursing homes

(or the way that we value, and devalue, our elders)

Around half of COVID-19 deaths in the United States have been among residents of care facilities, primarily nursing homes. As with our meat industry, this has been shining a light of media attention on some uncomfortable truths about modern society.

Several weeks ago I read an article – which I can no longer find – which argued persuasively that there is no ethical way to assign a different value to human life based on age. That is to say, it is no less tragic if COVID-19 or anything else kills an 85-year-old vs. a 25-year-old. This set me to thinking, as I couldn’t bring myself to agree. While I would certainly rather die at 75 than 45, it matters far less to me whether I make it to 85 or 95. I expect that my quality of life will be diminishing in those later years, and I hope to feel that I have lived a “full life” by age 75 if not sooner.

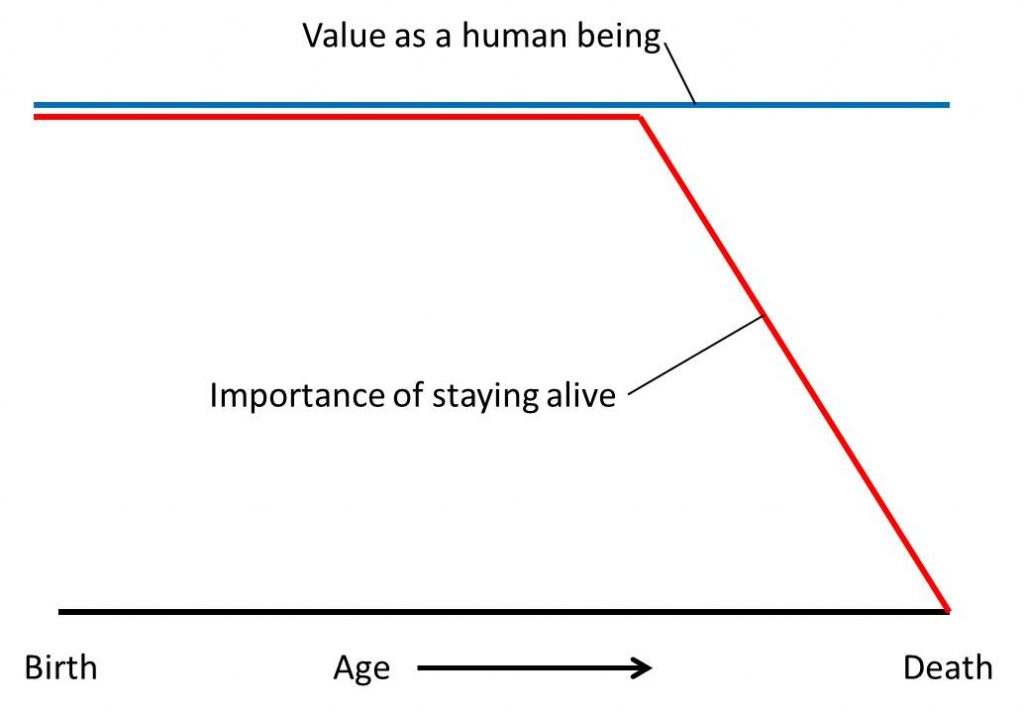

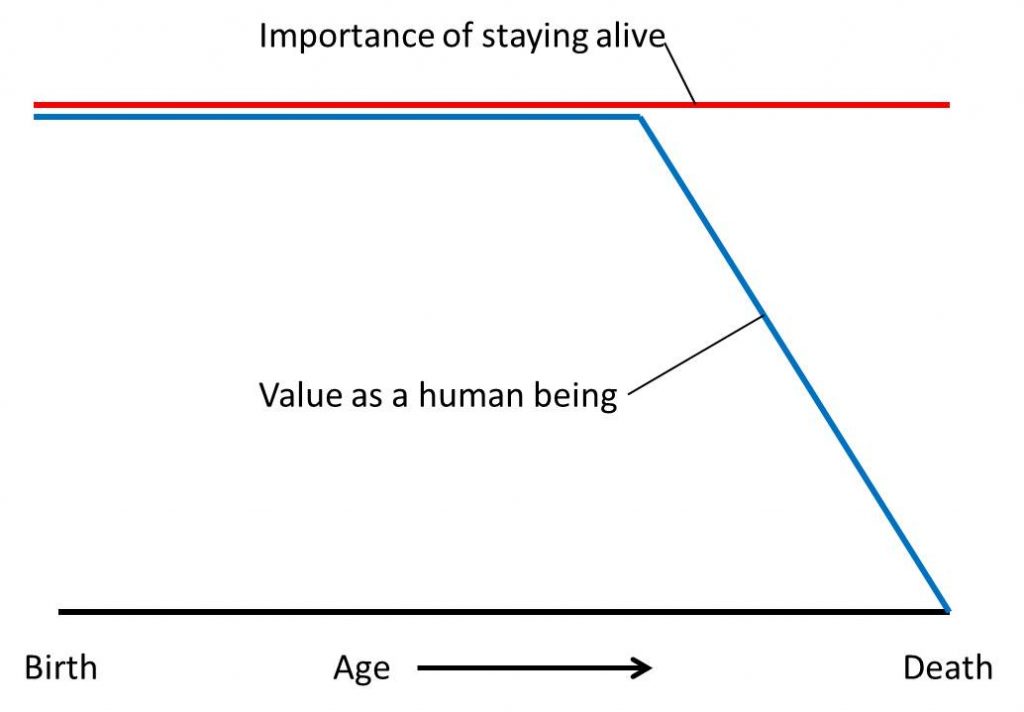

Pondering this further, I came to realize that we are conflating two different values in our relationship with our elders. The first, which I will call Importance of Staying Alive, reflects our readiness for death – both in our own minds and in the minds of our loved ones – and the lengths to which we are willing to go to prolong life. The second, which I will call Value as a Human Being, includes respect, appreciation, and inclusion in family and community – all of the ways that we express our love and acknowledge the humanity in each other.

In older times, I imagine that these values changed over time something like this:

Survival was of paramount importance for children, for parents, and for the duration of a career. Beyond that, added years were an unexpected bonus, and quality of life declined as aging set in. While death was always a sad occasion, it was less tragic when it greeted a life well lived than when it claimed someone in their prime. At the same time, elders remained in the care of their families, and their value was maintained. They were seated at the table, included in discussions of the day and revelries of the evening, and consulted for their expertise for as long as their mental faculties survived.

Having spent a fair amount of time in nursing homes, it seems to me that we have, through some complex mental gymnastics, gotten these values reversed in a most unpleasant way. In order to more fully join the rat race economy, and with the supposed justification of gender equality, we have devalued the economy of the home – traditionally “womens’ work” – that included at-home care for our children and our elders. We have outsourced these roles to underpaid and undervalued workers, who are still primarily women. It seems to me that it might have been a better feminist goal to shoot for equality in the home economy – dividing both breadwinning and child/elder care among men and women – than to sell out both genders to the patriarchal capitalist agenda of maximum employment. But that’s not what happened.

In order to make peace with our choice to send our elders away to assisted living and care facilities, we told ourselves a comforting story. They will be safer there, we told ourselves. In the care of professionals, their needs will be met better than at home, and their lives will be longer. And so off they went, into loneliness, to shuffle down the halls in a daily routine and play bingo with strangers, while family might visit once a week if they were lucky. And once they were out of our lives, their value to us declined. They were, for all intents and purposes, just waiting to die, but since we had sacrificed connection for safety we were no longer willing to accept their deaths.

Every day I read stories of the tragic toll of COVID-19 in nursing homes. Yet to me it is not the death that is tragic. The average duration of a nursing home stay, prior to death, is just over two years. Death is to be expected, and there are many in such a state of physical decline that it seems almost a mercy. What is tragic to me is that these people are all dying alone, and that their families are barred from visiting. Formalizing these restrictions only emphasizes their everyday reality: that most of these people die alone in normal times, and family visits are the exception rather than the rule.

When my father died in 2016, he spent two months in a nursing home before passing. This was a choice on my part and his, given that his decline was relatively rapid, his prognosis was poor, and it would have been difficult to retrofit his home to provide for both his comfort and a caregiver. So he moved into the home, but we stayed with him. Every day, while he was awake, Jean or I, or sister Barbara, sat with him. As death neared he asked not to sleep alone, and so every night for the last month one of us slept in the recliner in his room. We ate meals with him, brought food from his garden, sang him his original songs, wheeled him around the block in the late summer sunshine. It seemed a beautiful time, and yet his room was unique. The other residents seemed sadly abandoned by comparison, barely alive and mostly forgotten.

Had his decline happened in this time, we would have been barred from visiting, and we would probably have chosen to care for him at home. I am hearing numerous stories of elders being sprung from care homes in this time, so that they can be with family instead. COVID-19 is killing the narrative that our elders are safer in an institution, and with that narrative dead we can no longer justify abandoning them. That can only be a good thing.

It is my hope that this pandemic will help us to recognize that the rat race isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, and that the home economy has real value. Skilled nursing facilities serve a purpose – especially memory care and some other specialties – but we have done our elders a great disservice by prioritizing their survival over their value to us, their inclusion in our daily lives, and our expression of love and appreciation for them on a daily basis. Perhaps we might choose to make routine institutionalization of our elders a thing of the past.

One Response to COVID-19: Seeking perspective, understanding our response, and shining a light into dark corners