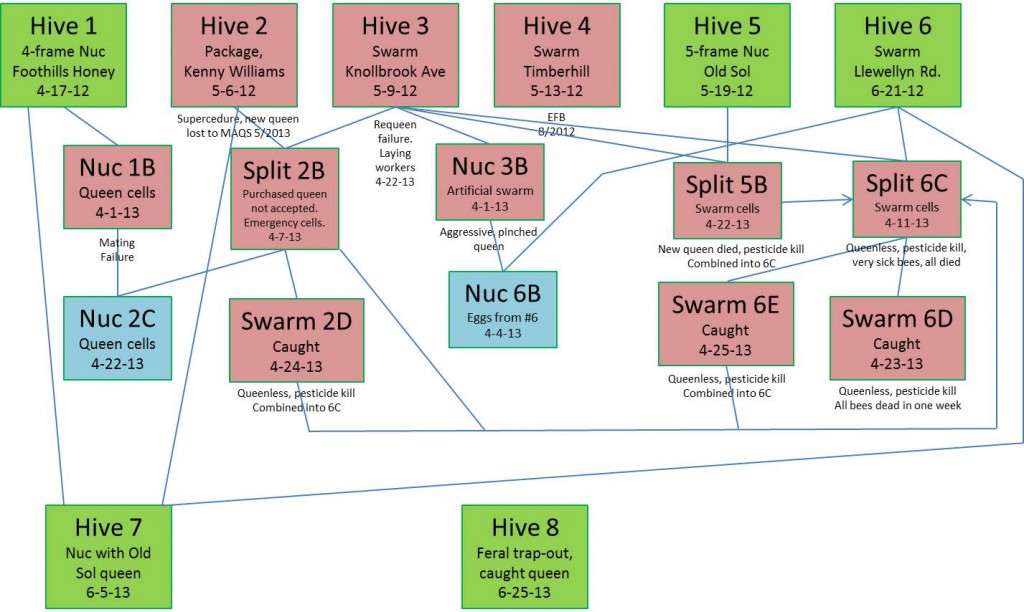

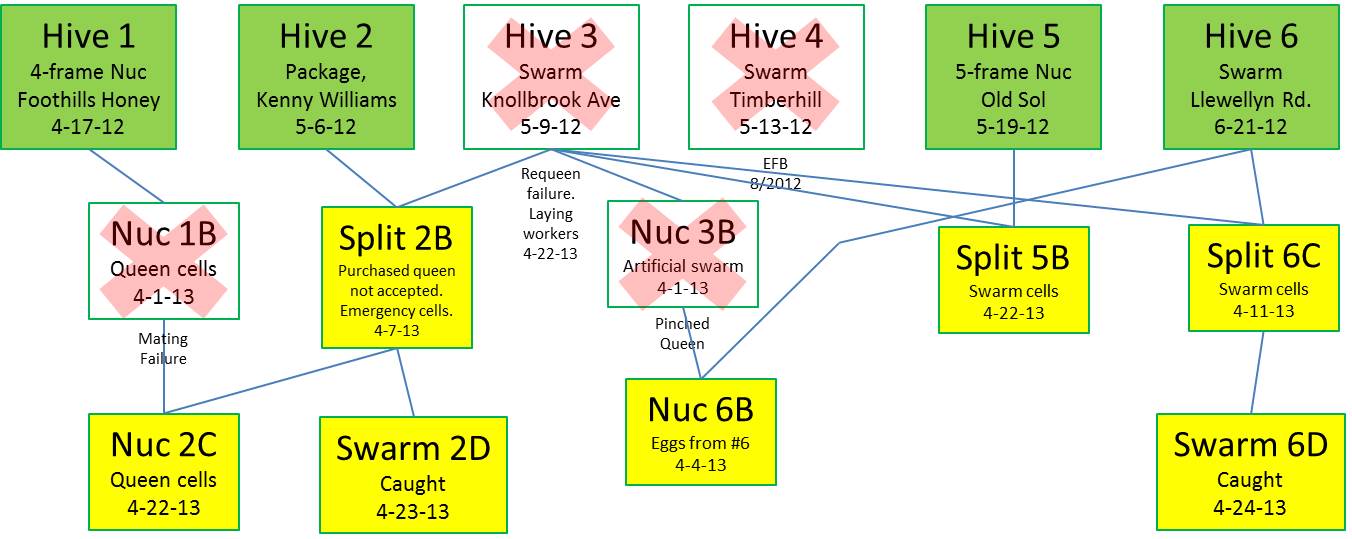

After losing most of my spring splits and swarms to a presumed pesticide incident (which I will write more about sometime), I found myself with a surplus of both hive boxes and drawn comb, and a need to fill those boxes with bees. So in early June, when I heard about bees in a tree northeast of town, I decided to take a look.

The hive looked healthy, if a bit on the small side. Based on entrance activity I would have guessed about one deep worth of bees. Their entrance was on top of a major yoke of a five-foot diameter oak tree, about nine feet off the ground. The landowner wanted the bees gone, as they were bothering her horses nearby, but she also didn’t want any harm done to her majestic 100+ year old oak. Time to try a trap-out.

A trap-out is, to quote Rusty of Honey Bee Suite, “a not very satisfactory way of removing a colony of bees.” In a traditional trap-out, a one-way exit cone is placed over the hive with a hive box nearby, and as foragers can’t get back in they accumulate in the box. Eventually the hive dwindles as more bees leave and provisions run out, and the queen either dies inside or absconds with the last desperate cluster. So yes, not very satisfactory. But it so happens that I procrastinate by reading the BeeSource forums, and I had come across the writings of one Cleo C. Hogan, Jr. from Kentucky. Cleo developed a trap-out technique that succeeds in drawing out nurse bees and in many cases even the queen. Enough beekeepers have adopted it that it is (somewhat) widely known as a Hogan trap, and Walter T. Kelley even sells a version of his design. I posted a question on the forum about the proper sequence of events, and Cleo quickly responded with his usual sound advice. As the discussion attracted additional participants, a fellow named Joseph from South Carolina chimed in with his own design and technique for getting the queen. Joseph has his trap for sale on eBay. I ended up using some aspects of both methods, with ultimate success.

The theory behind a Hogan-style trap-out is that the trap becomes an additional brood chamber. This is accomplished by connecting the trap directly to the hive via a sealed tunnel or passage and then adding a frame (or several frames) of brood (with no attending bees) taken from another hive. The brood draws out nurse bees to care for it, and if the queen is short on space to lay or wants to see who else is laying eggs in her hive she will come into the trap box. Joseph’s two additional suggestions were to add some emerging brood (because the queen prefers to lay in recently-emerged, cleaned cells) and to perform cycles of activating the one-way exit for three days before opening the passage for one day. The effect of the latter is to concentrate the majority of the population in the box, where the foragers will deposit nectar and pollen in the usual pattern around the brood. With brood and most of her workers elsewhere, the queen will begin to feel abandoned and move to where the bees are.

I modeled my tunnel and one-way exit on a design by T’s Bees, and integrated it into one of my swarm traps.

Tunnel design inside box, tunnel open.

Tunnel closed, bees must use one-way funnel. Bee demonstrating inability to get through.

The tunnel is built from 1×4 lumber, square with 3 1/2″ outside dimensions, and 7″ long to extend both inside and outside the box . I chose this size to match my swarm traps, which are built from a medium super on top of a 1×4 rim. It so happens that a medium plus a 1×4 is very close to a deep, and this allows me to use surplus honey supers as swarm traps (with deep frames) prior to the main flow, at which point I retrieve them and deploy them as supers. The tunnel closure is a square block of 1×4, and the funnel is shaped from #8 hardware cloth. The funnel tip could perhaps be a tad smaller. I never saw a bee go through it “backwards” but it certainly looked possible.

With the tunnel in place the box holds seven frames.

Tree side of trap box.

The outer tunnel, which attaches to the tree, has 3 1/2″ inside dimensions so as to fit snugly over the inner tunnel. I made it 16″ long with the idea that I would cut it to fit the geometry of the tree.

Large tunnel, cut on site to fit hive entrance.

Front of trap, bee entrance is 1 1/8" diameter.

The bees were emerging from a vertical crack at a major yoke in the tree. I was glad I cut the tunnel as long as I did, as I needed the length to extend out to where I could place the box. The bracket is built from more 1x4s, three hinges, and one piece of plywood. The angle brace has overlapping boards and can be adjusted 12″ in either direction, allowing the platform to be level despite mounting to a non-level tree trunk. Lag screws would be more secure, but in the interest of doing no harm to the tree I opted for ratchet straps, eventually using four of them to give the platform a capacity of 100 lbs or so without slipping.

Sealing gaps around the tunnel is an art. Initially I tried duct tape, which doesn’t stick well to tree bark. Then I stuffed the remaining cracks with paper. Finally I settled on landscape foam, which works great. I do, however, recommend stuffing paper towels in the gaps first and applying the foam at night or when the bees are not active. For the first 10 minutes or so after application the foam is sticky and traps bees that land on it.

I installed the tunnel on June 9 and gave the bees two days to get used to it before returning to install the box.

Tunnel installed on tree.

Gaps sealed with expanding foam.

Trap in place, right before I took it down. 5:00 am, June 30, 2013.

Trap from the other side.

Strategy time. I installed the box with a single frame of eggs and open brood, leaving the tunnel open. For the next six days I checked it occasionally, looking for the queen. I found the brood frame covered with nurse bees and the field force packing nectar into the other frames, but no sign of the queen or new eggs. By this point Joseph had joined the online discussion, and his ideas made sense to me so I decided to try them. On June 18 I brought out two more frames of brood, one capped and soon to emerge and one of eggs and young larvae. I then closed the tunnel and left it for three days.

On June 21 I returned to open the tunnel, finding all three brood frames now covered in nurse bees. The next day, on the way to my birthday party, I returned hoping to find an early present of the queen. No such luck, though as it turns out she may have been there and I just missed her. In any case I didn’t see new eggs yet, and I closed the tunnel for another three-day stint.

On June 25th I returned to open the tunnel and found the trap nearly filled with bees, and new eggs! Given that the one-way exit was activated I figured that the queen couldn’t get back in the tree so she must be in the box. It took a bit of searching but I soon found her – a rich dark brown and not particularly large as queens go but certainly healthy.

I moved her and all of the bees into an empty deep to bring home and refilled the trap with more drawn frames. As it turns out this may have been a mistake, and the wiser course may have been to leave the queen in the trap for another 5-6 weeks, adding a super, and allowing all of the brood still in the tree to emerge and join the queen in the trap. But that would require absolute faith in my one-way funnel, lest the queen find her way back through and my opportunity be lost. This being my first trap-out, I decided to take the queen while I had her in sight. I set the ~six frames of bees up in my home apiary where they soon reoriented and resumed normal bee life.

These feral bees have all colors in their ranks from yellow to brown, likely the result of the queen mating with a diverse collection of drones. They are also remarkably gentle to work with, so long as they have their queen. Queenless bees are often angry bees, and three days after I removed the queen I got a message from the landowner that the bees were buzzing her and would I please remove more of them. So I returned after sunset, opened the box, and quickly collected 15 stings on my wrists and ankles despite a full suit and gloves. I duct-taped the stingable parts and went back at them, moving about 2 1/2 frames of very unhappy bees into a nuc and replacing the frames in the trap. Lesson learned: don’t work angry bees at night without smoke.

The next morning I reunited the angry bees with their queen and found another message from the landowner: bees still angry. too angry. can’t work horses. can I put out poisoned honey? Now any beekeeper knows that pesticides kill far too many bees these days, and poisoned honey is a good way to kill or or at least weaken any hives within two miles. At this point I had the queen and probably 75% of the bees: all of the foragers, a majority of the house bees, and enough nurse bees to tend three full frames of brood. I couldn’t come up with a good way to make the bees less angry short of giving them their queen back, and it would still be another four weeks before all of the nurse bees and still-to-emerge brood in the tree entered the trap, leaving the tree empty of bees.

Four weeks of bee aggression was too much to ask of the landowner for an extra pound or so of bees, so I reluctantly agreed to exterminate. Before sunrise this morning, I removed the trap (with another frame of bees collected in it), emptied a can of non-synthetic hymenopteran killer down the hole, and sealed the entrance with another can of landscape foam. I feel bad for the dead bees and the unknown amount of honey now permanently sealed inside (I had hoped to bring another hive to rob it out after completing the trap-out), but I got 75% of the colony, including the queen, and the landowner got rid of her bees.

So…trap-outs are fun! One Kentucky fellow on BeeSource said getting the queen felt just like shooting a ten-point buck, and I know what he means though I have never hunted myself. A few things I will remember for next time:

- Trap-outs require a lot of visits and are best done within 10 miles of home. This one was right about at the 10-mile cutoff.

- Trap-outs are likely to make bees more aggressive for a time, particularly if the queen is removed. In the future if aggression is a concern I may try to leave the queen in the trap until the trap-out is complete, thus keeping the colony intact and (hopefully) docile.

- Don’t work bees in the dark. This is one of those warnings you hear from experienced beekeepers with a little smirk that says “try it, you’ll see.” Bees in the dark don’t fly around and head-butt and try to get at your face only to be stopped by the veil. They simply fly directly to the first soft surface they can find and plant their stingers, stinging straight through fabric that has never been stung through before.

- It’s a myth that you can’t get the queen. There are probably some cases, especially in buildings, where the distance from the entrance to the combs is too far for the queen to ever move, but judging from the writings of Cleo and Joseph and from my own very limited experience, getting the queen is not just possible but quite likely and with patience nearly guaranteed.