My apologies to those who watch my blog to read about bees – it’s been too long since I posted about them. When last I posted, they were booming and swarming, and my five overwintered colonies had become 12. Unfortunately with bees, the good times usually end. In our case they ended around April 25th, when the bees got into something toxic. My best guess is an insecticide inadvertently or ignorantly sprayed on flowers they were visiting. Regardless of the cause, bees started dying. At first we noticed twitching bees around the entrances, then piles of dead bees, then, in the worst cases, piles of dead bees in the hive with only a few sick-looking bees remaining. In this way we lost all three of our swarms and three of our splits. One died outright, and the other five we consolidated into one colony that proceeded to dwindle and die. None of their virgin queens survived to lay eggs.

From 12, we were down to 6. Two of these were nucs with virgin queens that we had promised to friends. Those queens made it, and although they both suffered from high forager attrition during the pesticide kill, they both went on to build up. From the reports we hear, one is now a booming, healthy hive heading into winter and the other sadly got robbed to oblivion last week. So we were back to four in the middle of May, and all of these had some amount of dead bees in front from the pesticide impact. In the best shape were two artificial swarm splits, which at the time of the pesticide exposure had a queen, brood, and lots of nurse bees but almost no foragers. Hive #1, the only one that we managed to keep from building swarm cells, had a full super of honey already, but over half of the foragers died leaving it at half-strength heading into the main flow. That leaves only #2, which had a failing queen undergoing supercedure. Thanks in part to excessive drone brood, we had mite problems in #1, #6, and #2 which we addressed with Mite-away Quick Strips. These are known to kill queens, and while the established queens in #1 and #6 pulled through fine, the just-started-laying supercedure queen in #2 perished.

In early June, Karessa announced that she had an Old Sol queen for me – one that I had ordered and then later thought I cancelled though it turned out I needed her anyway. I didn’t have many bees to spare though, so I took one frame of brood and nurse bees each from #1 and #6, a couple of frames of stores, and a frame feeder, and introduced her to this little nuc. Then when she had been accepted for a week and #2 was definitely queenless, I combined them in with the newspaper method. This also gave them a fair amount of honey and pollen stores left from Hive #2. They built up well through the flow, and with help of some fall feeding will be going into winter as a strong double deep. They are Hive #7.

Hive #8 came to be as a trap-out from a tree, which is a separate story already told on this blog. They will also be going into winter as a strong double deep, though they had very little honey as I captured them after the main flow. I am feeding them as much as they will take and am hopeful that by the end of September they will have enough for winter.

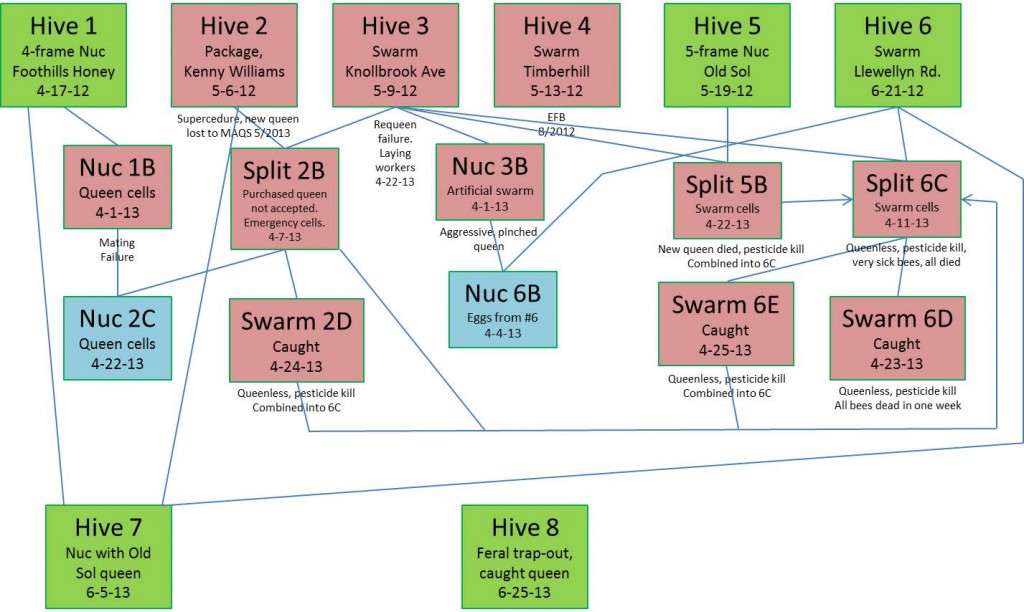

If all of that was a bit confusing, here is an equally confusing ancestry diagram for our hives. Red ones died (or at least the queen died), blue ones were sold, and green ones are alive and well at our home apiary.

Honey:

When the spring swarms and splits crashed, we were left with two supers partially filled in good April weather. We extracted these, yielding 15 pounds of tasty maple-and-other-things honey. The three surviving hives built up well into and through the main flow, filling one super each. On July 28, we extracted 84 lbs of honey from these, with an extra 6 lbs or so saved as cut-comb honey. That’s a total of 100 lbs of extracted honey, most of which is going into mead.

Lessons learned this year:

- Opening the broodnest with foundationless frames to prevent swarming is a bad idea, because they will draw 100% drone comb and breed mites. I still like the idea of opening the broodnest, but will try doing it with foundation or empty drawn comb next year instead.

- Candy-plug queen introduction does not work well in booming, swarm-ready hives. We lost two $25 queens in a week this way. In the future we will keep the candy covered until the bees show signs of accepting the queen, or else we will introduce the queen to a nuc and then do a newspaper combine.

- Heating the honey shed to 95 degrees to help the honey flow is a good idea, but only if it is aired out BEFORE beginning extraction. Once extraction begins, the cloud of bees at the door means the door must remain closed. If the room is still 95, it stays that way until you are done. We might also try extracting at night when the bees are not flying.

- Shaking out a three-box hive of laying workers during swarm season is a bad idea. The recipient hives will be overpopulated and swarm, and the laying workers might kill the emerging virgins. Next time we will try just giving them a frame of eggs weekly until they raise a queen.

- Outyards are a good idea. Not only do you diversify your honey flavors (very important when your primary goal is a creative variety of meads), but you eliminate the possibility of a single pesticide incident hitting all of your bees. Next year we will have bees in two or possibly three yards.

- Trap-outs are a good way to get feral bees. I hope to do one or two next spring now that I have the gear.

- Bees really don’t like ApiLife Var. My first application to four out of five hives in August had most of the bees vacating the hive during the day, with some remaining clustered outside even at night. Because of this excessive disturbance I used two rather than the recommended three treatments. Mite drops were not particularly impressive compared to Apiguard and especially MAQS.

- MAQS (Mite-away Quick Strips) really work. Over a thousand dead mites on the bottom board in two days, and almost no mites in the hive thereafter. They also kill nearly all of the open brood. Next year I will use them, if necessary, in late March/early April rather than late May, giving the bees ample time to recover from the setback and possibly helping to prevent swarming. I might also use them in the fall, as the thymol treatments have been disappointing.

The bottom line: we started the year with five healthy hives, and after a great deal of kerfuffle we are going into the winter with five healthy hives. All in all not too bad, I would say…