For the second year in a row all five of our hives successfully overwintered. There is some degree of luck involved, as queen loss or disease can affect any hive at any time. Even so, we are beating the odds (nationwide hobbyist average of 30% winter loss) by enough that I think we are doing something right.

Our strategy:

- Control moisture. We built moisture quilts two years ago: screen-bottomed inner covers filled with 2″ of cedar chips that absorb moisture rising to the top. The chips get wet and the bees stay dry. The quilts also allow us to keep tabs on the populations in the winter: the wetter the chips and the larger the wet area, the larger the cluster below.

- Manage mites. Thymol (from thyme or oregano) in August after honey harvest, oxalic acid (present in rhubarb and spinach) in early December. We treat only colonies that need it; the oxalic acid in particular is highly effective on mites with minimal effect on bees. We keep purchasing hygienic queens and hope to need fewer treatments going forward, but we have so far found it essential to keep mites in check.

- Plenty of food. Most hives have ~40-60 lbs of honey in the upper brood box after honey harvest, but with no good fall nectar sources in our climate a fair amount of this is consumed in September and empty cells remain as the brood nest contracts to winter size. We feed 2:1 sugar syrup in September until there are almost no empty cells in the hive. With that amount of stores we don’t need to worry about feeding in winter or spring.

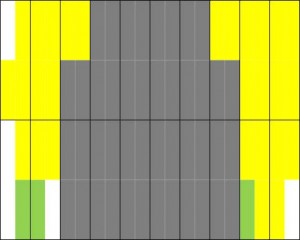

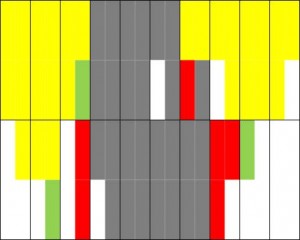

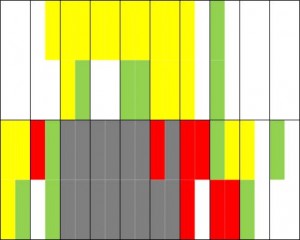

Last weekend we moved the hives: three to the Watershed Homestead and two to Goosefoot Farm north of Albany. Yesterday, at 60 degrees, we inspected the watershed hives. The diagrams are the same as last year: yellow = honey, green = uncapped stores or uncured nectar, red = pollen, gray = brood, white = empty.

Hive #5

Hive #5 started as a nuc from Old Sol two years ago, picked up from John Jacob himself at a freeway rest stop in Eugene at 1 in the morning. After producing a full super of honey last summer, the queen stopped laying in early September. Six weeks later, in our last fall inspection, there were still no new eggs to be found and we feared that the hive was queenless. We’re not sure if they superceded in the fall or if Her Majesty simply took a long vacation, but we were heartened to see them still alive and bringing in pollen in late winter, and we assumed they must have a laying queen.

We found a beautiful big queen in the middle of 12 frames (!) of brood, building up fast with honey remaining on the outer edges. This colony is our best bet for getting some maple honey when the trees bloom in a couple of weeks. Of some concern, this hive had almost no pollen stores. Usually our philosophy is to avoid supplementing pollen so that the bees adjust to natural availability, but in this case we will be adding a pollen patty as soon as we can find one.

Hive #6

Hive #6 started as a virgin swarm that took up residence in one of our bait hives around the summer solstice of 2012. The queen, going on two years old now, is still laying a beautiful brood pattern. With brood on eight frames, this colony is building up well and has much more pollen stored than #5. Our most defensive hive, this colony needs a bit more smoke and has been known to send out stinging guards if we stand too close to the entrance.

Hive #8

Trapped out of a huge oak tree along the Willamette near Albany, these dark, docile bees seem to be able to keep mites under control without much help from us. With brood on only four frames they are 2-4 weeks behind the other hives in terms of spring build-up, and it will be interesting to see if they remain small or if they are simply late bloomers. Aside from the smaller population, the colony and queen appear healthy.