For most of the past year my writings have focused on escaping from the dominant narrative, which is largely shaped by those who have wealth and power and is designed to distract and prevent the rest of us from staging a real confrontation with that power.

At the same time, I have occasionally offered my perspectives on the Covid-19 pandemic, and I am thoroughly convinced that much of the world reacted in a highly irrational manner: imposing severe restrictions on society that are almost certain to cause greater long-term harm and loss of life than the virus itself, and then doubling down on those restrictions even when it became clear that they had little to no effect on viral transmission. Furthermore, the level of fear surrounding a virus that killed at most one out of 350 people was, quite frankly, shocking to me.

The prevailing narrative among those who oppose the mainstream Covid story is that our overreaction constitutes an extreme form of disaster capitalism, as described in Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine. In short, governments and corporations magnify, exploit, and sometimes even create crises and states of emergency in order to consolidate power and enact legislation that curbs personal freedoms. In many ways, the shoe fits. Covid lockdowns have greatly enriched the billionaire class while resulting in the closure of thousands of small businesses. Klaus Schwab and others associated with the World Economic Forum are on tape saying that the Covid crisis represents a window of opportunity to carry out the “Great Reset,” which in many ways amounts to corporatist feudalism. Censorship is ratcheting rapidly upward, along with restrictions on movement and freedom of assembly.

All of this may be true, and yet I don’t believe that it tells the whole story. It may even be harmful, in that it gives the narrative managers more power than they deserve, and thereby can make the rest of us feel like manipulated pawns. It inspires us to blame others for fear that is ultimately within ourselves, and thereby to avoid looking too deeply at where that fear is coming from.

Looking back over the past 15 months, it is clear that the fear surrounding Covid was not entirely, or perhaps even primarily, a top-down phenomenon. This was not like Saddam’s nonexistent WMDs, where people were only afraid because they were told repeatedly by authority figures that they ought to be. When the virus began spreading in communities and countries, citizens begged their government experts to tell them what they could do to stay safe from this new threat. Those few brave epidemiologists, like Sweden’s Anders Tegnell, whose training and experience taught them that the wisest course likely was to focus on protecting the most vulnerable while allowing the virus to spread and build immunity, faced intense criticism not just from would-be controllers but from millions of everyday people. And I’m far from convinced that this happened because those everyday people were brainwashed into being fearful by powerful narrative manipulators.

Woven throughout the Covid saga has been a theme of science-as-religion. Results and even predictive modelling rapidly crystallized into dogmatic truth, at which point no amount of countervailing evidence had any effect, much to the frustration of many actual scientists. Masks Save Lives (based on a few small studies, but not well supported by epidemiological evidence or past research with other respiratory viruses). Lockdowns Save Lives (despite the fact that later comparisons found no correlation between severity of restrictions and level of illness/death). The Vaccines Are Completely Safe (even though they are based on a novel technology and have been tested less than any other vaccines in recent history). And so on…

It is this religious element that deserves more attention, because the Covid-19 pandemic represents in many ways a crisis of faith. In order to discuss this, however, we need to expand our definition of religion. We need to understand that it is impossible for human beings to exist without religion, because religion is ultimately not about belief or disbelief in God or gods. It is, rather, about the way in which we answer deep questions about the nature of our existence, and we cannot comfortably exist without answers to those questions. I have written about this before, and I offer this excerpt from my 2017 essay, Sustainable Religion and a Society in Crisis:

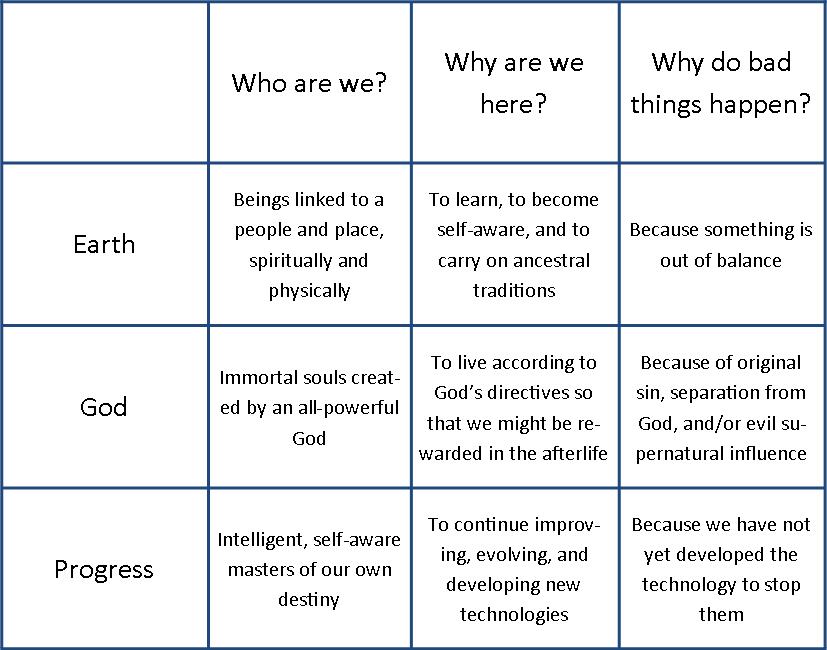

Religion means many things to different people. In its strictest sense, it refers to codified systems of spiritual belief and practice. However, each person must inevitably come to a sense of identity, regardless of whether they subscribe to a formal “religion.” For the purposes of this discussion, I will define “religion” as a system of beliefs or vision of reality that seeks to answer the following three questions:

Who are we?

Why are we here?

Why do bad things happen?

It is important here to note that a concept of “God”, or even a concept of a supernatural force, is not required to answer these questions. It may seem strange that I choose to lump secular philosophies in with religion, but I hold that these philosophies ultimately serve the same purpose in terms of helping believers make sense of, and choose to interact with, the world we inhabit.

Ignoring a great many traditions that do not fit this mold, I find it useful to divide answers to these questions into three main groups: Earth-based religions, major monotheistic religions (e.g. Islam, Judaism, Christianity), and beliefs rooted in modern technology. I will call these groups, respectively, Earth, God, and Progress.

In that essay, I also attempted to outline the way in which these three classes of religions answer these three existential questions:

It is clear to me that a significant proportion of people alive today, including many who subscribe to God-based religions, are believers in Progress. Last summer I wrote a series of essays unpacking the problems with neoliberal economics, which was made more difficult by the fact that the prevailing culture has eschewed any descriptive name for this economic system, preferring instead to simply see it as “the way things work.” Similarly, most people who believe in Progress will deny any such thing, claiming instead to be secular and to “follow the science.” It is difficult to discuss important concepts for which we do not have widely accepted language. Nevertheless, I feel strongly that much of our irrational response to Covid-19 is rooted in a widespread belief in Progress.

A few days ago, a college acquaintance posted the following on his Facebook page:

Nothing betrays an absolute inability to think like idealizing pre-modern life, yes it was very simple and idyllic and if the harvest failed half your kids died. I feel like this is kind of true for people who idealize farm life as well.

To which I replied that nothing betrays an inability to think like freaking out and shutting down society over a virus that kills at most one out of 350 people, and he responded with:

Well, I reckon anyone who wants to move to the middle of Alaska to live a pre-modern lifestyle is welcome to do it. Heck, they even got whole TV shows where they tell some Boy Scout type that he/she can have a million dollars if he can live alone in the wilderness off the grid for a month. And a lot of them don’t make it. But it is entertaining to see the poor dang fools try to earn their spurs.

I have had other interactions like this, in which someone attempts to make a moral point by stating that The Past Was Bad. It might be famine, or smallpox, or human slavery, or bloodletting, or witch-burning, or surgery without antibiotics or anesthetics, or any number of things, but the point is to inform me in no uncertain terms that I have committed a cardinal sin by suggesting that some technology or practice from the past might be preferable to one currently in use.

I might, of course, respond with a note about cluster bombs, or Mutually Assured Destruction, or climate change, or sky-high rates of depression and addiction, or consumerism, or CAFOs, or outsourcing jobs to sweatshops overseas. But this inevitably falls on deaf ears, because The Past Was Bad, period, end of story. This is not a statement of reasoned assessment; it is a statement of religious conviction, akin to “Jesus died for our sins” or “Satan is evil.”

That’s not to say that I believe the past was especially good; rather, I don’t assign morality to the dimension of time. That was then, this is now, and we are just people doing the best that we can when we happen to be alive. Sometimes going back to an older way of doing things can have benefits, sometimes modern technology has clear advantages.

With this in mind, I can add a fourth column to my comparative religion table: What is the domain of evil?

In Earth-based religions, evil lurks in particular physical places: in dark forests, in deep lakes, in treacherous swamps. There are places where one ought not to go, or ought to tread very carefully.

In God-based religions, evil lurks in our thoughts, or in a spiritual dimension accessible to our thoughts. Those who are evil have succumbed to the temptation of the devil, or have made choices to ignore the will of God.

In the religion of Progress, evil exists primarily along a temporal dimension. The Past Was Bad, the present is better, and the future will be awesome.

It is perhaps not surprising that many affirmations that The Past Was Bad are medical in nature, because it is through treating and preventing formerly fatal conditions that technological progress has been most god-like. Prayer typically failed to prevent smallpox and polio, but vaccines could. Prayer failed to prevent death from an infected wound, but antibiotics could. It is indisputably true that advances in medical science – mostly in the post World War II era – prolonged human life and reduced physical suffering.

Although I have not read a historical analysis of belief in Progress, my impression is that it is a relatively recent phenomenon, dating back to the 1940s-50s. Prior to that time, people appreciated technological advances – steamships, railroads, electricity, personal vehicles – but they did not, on the whole, believe in them or allow technological progress to give meaning or value to their lives. That has changed in recent generations. Belief in traditional religions declined, and belief in Progress exploded. Antibiotics and vaccines were heralded as reasons to believe, praised by those who preached the gospel. Historical timelines were conveniently rearranged and cherry-picked to progress linearly from the barbaric past to the civilized future, from ape to cave man to farmer to office worker, from cannibal to slaver to proponent of human equality. As any scholar of history knows, this simplistic vision brushes aside the rise and fall of many great civilizations, with repeated movements toward and away from societal complexity and human equality.

In place of heaven, Progress-ites constructed a Star Trek vision of the future, with humans moving into space, across the Solar System, and ultimately across the galaxy, communicating instantly across vast distances, tapping into effectively infinite energy sources, curing any disease, and ultimately overcoming death itself through medical technology, or cryogenics, or uploading consciousness to a digital brain.

In place of hell, Progress-ites constructed a disease-ridden, barbaric past in which life was nasty, brutish, and short, and to which we must never, ever return. Those who chose not to follow the latest technologies, who preferred a simpler, more rural lifestyle, were regarded as “backwards” unbelievers and therefore unworthy of respect.

In the seventy years or so since this vision unfolded, we have made it to the moon a few times, not yet in-person to Mars (which, it turns out, would be a rather boring and inhospitable place to live), and we have more or less concluded that interstellar travel violates the laws of physics. We got the Internet (instant global communication), but not the infinite energy, and in fact it is becoming clear that available energy will be declining in the near future. We got life-extending medicine, but so far no hope of overcoming mortality, and at the cost of devoting almost 20% of our economic output to the medical industry while also ensuring that a greater proportion of people live to a ripe old age, thereby experiencing a greater proportion of our lives in a state of decrepitude. In short, we got technological progress, but dictated more by the limits of physical reality than by our grandiose religious vision.

As a result of the widening schism between the future we have been promised and the future we are actually getting, the religion of Progress is experiencing a crisis of faith on a massive scale. This can, from my perspective, help to explain many problematic aspects of our current existence, from Trumpism to growing wealth inequality to irrational decision-making to censorship. That will be the focus of another essay. For now, though, I want to examine the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of a crisis of faith in the religion of Progress.

Covid-19 is the first major pandemic of the age of Progress. As pandemics go, it is relatively mild, killing at most one out of every 350 people and increasing all-cause deaths by 5-15%. From an epidemiological perspective, global pandemics are inevitable, as viruses continually evolve and cross species boundaries. The natural recurrence interval for a pandemic of this magnitude appears to be somewhere on the order of 50 years.

From the perspective of Progress-ites, however, this disease is quite literally a bat-virus-out-of-hell – hell being, in this case, the evil past inhabited by deadly infectious diseases that have been tamed by modern technology. Therefore we must Do Something. We must create a vaccine as quickly as possible, and we must all do our part to stop the spread until that point. This perspective helps to explain the level of fear. It helps to explain the level of religious commitment to actions – like wearing cloth masks – which we firmly believe are effective even in the absence of convincing scientific evidence. It helps to explain the level of vitriol hurled at Anders Tegnell and other epidemiologists who suggested that working carefully toward natural population immunity would be the wisest course of action. Asking a Progress-ite to allow an infectious disease to spread is akin to asking a Christian to welcome a Satanic temple to their town, or asking a pagan to move to Mirkwood Forest. To do nothing, in the face of an infectious disease, is blasphemous. It is anathema to the core of their beliefs. It Must Not Be Allowed. Those who suggest otherwise must be silenced.

This perspective also helps to explain the narrative of how horribly horrible Covid deaths are. The numbers are compared, with no sense of irony whatsoever, to deaths from terrorist attacks, mass murder, and war. They are never compared to deaths from cancer, or heart disease, or dementia. The virus, from within the Progress narrative, is evil, and anyone who knowingly allows it to spread, or fails to take largely faith-based precautions, or – heaven forbid – infects someone else, is evil by association. Unforgivably evil like terrorists or murderers. As an apostate from the religion of Progress, I find this all very strange. Most deaths are prolonged and unpleasant, and Covid is nowhere near the top. I watched my father wither away, in severe pain, from metastatic bone cancer over six months. I watched my grandmother slowly lose her ability to recognize her family, her husband, even to move or feed herself from Alzheimer’s over six long years. I would wager that if I could ask either of them, in the afterlife, if they would have preferred to die of a 2-3 week respiratory infection, they would probably say yes in a heartbeat.

This perspective further helps to explain who is especially concerned about Covid and who isn’t. There is a significant overlap between self-styled “progressives” and Progress-ites. And indeed fear has been highest in the places that have most deeply embraced the religion of Progress: the liberal cities, the “blue” states, academia, the tech industry. Meanwhile fear has been lowest in the rural hinterlands, in working-class neighborhoods, in (God-based) religious communities. People who do not subscribe to the ideology of Progress are, it seems, much more able to rationally weigh the risks and to make decisions accordingly. It is possible, in this context, to view the culture wars between the Covid-afraid and the Covid-unafraid as a sort of ideological crusade pitting the righteous (who perform the appropriate banishing rituals in public) against those who would invite the devil into their homes, who see no evil and fear no evil. That might be taking the analogy a bit far, but I think it is important to understand the role that belief plays in shaping our individual Covid reactions, and the role that the religion of Progress plays in shaping that belief.

This isn’t to say that the disaster-capitalism approach to understanding Covid is wrong. Personally I find it equally compelling. It is entirely possible that a belief in Progress leads to an irrational fear of evil infectious disease and a demand for savior vaccines, and also that this fear is exploited by governments and corporations wishing for greater influence and control. It seems likely that the media are intentionally choosing to promote fear, as they nearly always do, while at the same time they are acting more as fear-enhancers than fear-creators, with the fear already latent within Progress-ites. It also seems likely that the elite, the ultra-wealthy, the Davos crowd are themselves devout believers in Progress, in which case their authoritarian lockdown recommendations may be rooted as much in their own fear as in a conscious desire to manipulate society for their ends.

The religion of Progress has a fatal flaw, which is that its heaven and hell (future and past) are entirely within the physical world, and therefore (unlike, say, Christianity) disprovable by physical events. In brief, Progress requires underlying progress. And as progress stutters to a halt, energy availability declines, and pandemics continue to circulate, Progress-ites will experience increasing cognitive dissonance and ongoing crises of faith. They will likely engage in panicked, irrational, and sometimes violent behavior. Eventually they will abandon Progress and seek other answers to life’s existential questions. And depending on what answers they find, the world may or may not be a saner place. But regardless of what comes next, I think it is safe to say that belief in Progress will be an increasingly untenable choice moving forward.

7 Responses to A Crisis of Faith