Toward a More Equal America, Part 10

We tend to think of politics in terms of voting on bills and taking positions on issues: debating, for example, exactly under what circumstances abortion or capital punishment should be allowed, or what types of guns are protected under the Second Amendment, or how much money to allocate to highway maintenance or education. In normal times, only a minority of citizens engage deeply with these matters, with most preferring to trust their representatives to sort things out while getting on with their lives.

At a deeper level, however, politics is about collectively deciding exactly what sort of society we wish to inhabit. At times like the present moment, when the structure of society is unstable and shifting, more people begin to tune in and take part, aware that the rules of the game of life are changing.

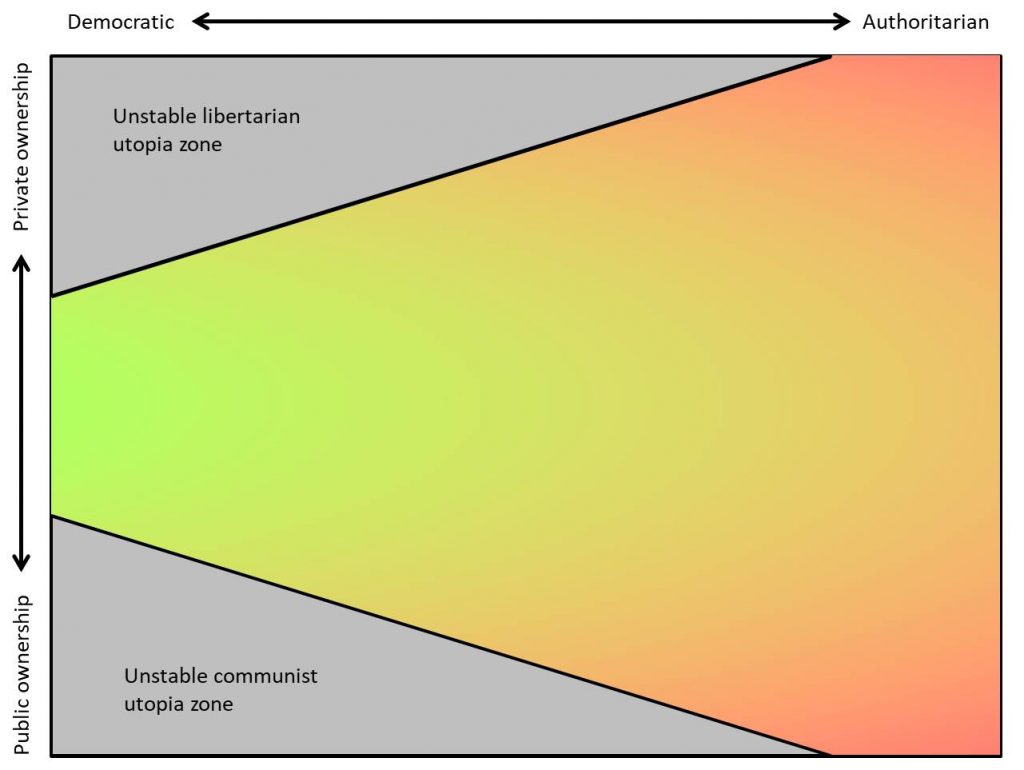

To make sense of where we are, where we are headed, and where we might be better off going instead, I find it useful to look at human societies along two axes – a plane of political possibility.

On the horizontal axis, societies can range from fully democratic – in which every person is granted a voice and a vote – to fully authoritarian – in which most people have no input into governance. On the vertical axis, societies can range from complete public ownership – in which all private industry is prohibited – to complete private ownership – in which the free market is viewed as the highest ideal in all circumstances.

Most of us, if given a choice, would prefer to live in a democratic society in which our concerns are heard and our voices are valued, rather than in an authoritarian society where the dictates of government must be obeyed under penalty of death. The ideal position on the vertical axis is somewhat more up for debate. Communists and socialists cite Karl Marx and wax poetic about egalitarian utopian “workers’ paradise” societies in which everyone works for the benefit of the whole. At the same time, libertarians and free-market devotees cite Ayn Rand and wax poetic about societies in which healthy competition drives innovation and assures that all of our needs and wants are fulfilled.

My perspective is that the ideal society is somewhere in the middle. Private ownership leads to competition, motivation, and innovation. Public ownership carries a mandate of acting in the common interest but can also lead to bureaucratic ossification and stifling of creativity. Which of these is preferable depends on which aspect of the economy we are talking about.

Back in Part 3 I introduced ethical red flags in the development of a market economy.

Ethical red flag #1: People will pay almost any price within their means to meet their basic needs, if there is no other option.

The upshot of this is that private enterprise – with its associated profit motive – will only work toward the common good when businesses are in competition AND demand is flexible.

Consider, for example, car manufacturers. Any business that can build vehicles can compete, and if prices are too high no one will buy them – they will move closer to work and take the bus. The result is that cars are priced reasonably relative to the cost of construction, and there are many options available catering to all niches from saving money to saving fuel to hauling large families to showing off status. A government-owned car manufacturer, on the other hand, would be tasked with providing the greatest utility to the greatest number and so would churn out millions of identical, no-frills models that would give little joy to their owners, and costs might even be higher without a competitive drive toward greater efficiency.

On the other hand, consider our water supply. It makes no sense for a town to have more than one set of pipes, so competition is not an option. Furthermore, without it we cannot survive, so we would buy it at any price even if it drove us to bankruptcy. And it’s just water; we don’t really want the option of extra-fancy oxygen-infused water, or blessed holy water, or 99.999% pure deionized water piped into our homes. It’s easy to see that private industry in this circumstance would be motivated to gouge buyers on prices and maintain infrastructure at a bare minimum level to maximize profits, while public ownership tasked with supplying a common good at a fair price would work much better.

So it is that most countries have private car manufacturers and publicly-owned municipal utilities tasked with delivering clean water. Unconstrained by ideology, democratic societies naturally adopt this blend of public and private ownership. Societies – or groups within society – that go religiously all-in on public or private ownership are either short-lived or else must become authoritarian to enforce their ideology against the will of the people who quickly realize its failings.

Very few of the communes of the 1960s and 70s lasted more than 10 years, and an attempted libertarian utopia in Vermont went predictably and somewhat hilariously awry. Communes must decide everything as a group, which leads to endless meetings and ultimately to conflict when some people’s creative or innovative ideas threaten cohesion or serve to privilege themselves above others. Libertarian communities cannot come together to solve shared problems, and so descend into spirals of blame and neglect.

This phenomenon – that attempts to organize democratic society around purely public or purely private ownership are doomed to failure – also helps to explain why there are no socialist utopias. Human nature aspires to some level of competition, innovation, and individual uniqueness, which inevitably leads to a greater level of autonomy and private enterprise unless this is forcefully forbidden by an authority under threat of punishment. Societies that follow an ideology into the gray areas of the political plane either relax their ideology and embrace a balance of public and private ownership, or else move rapidly toward authoritarianism to preserve the ideology against the countervailing force of human nature.

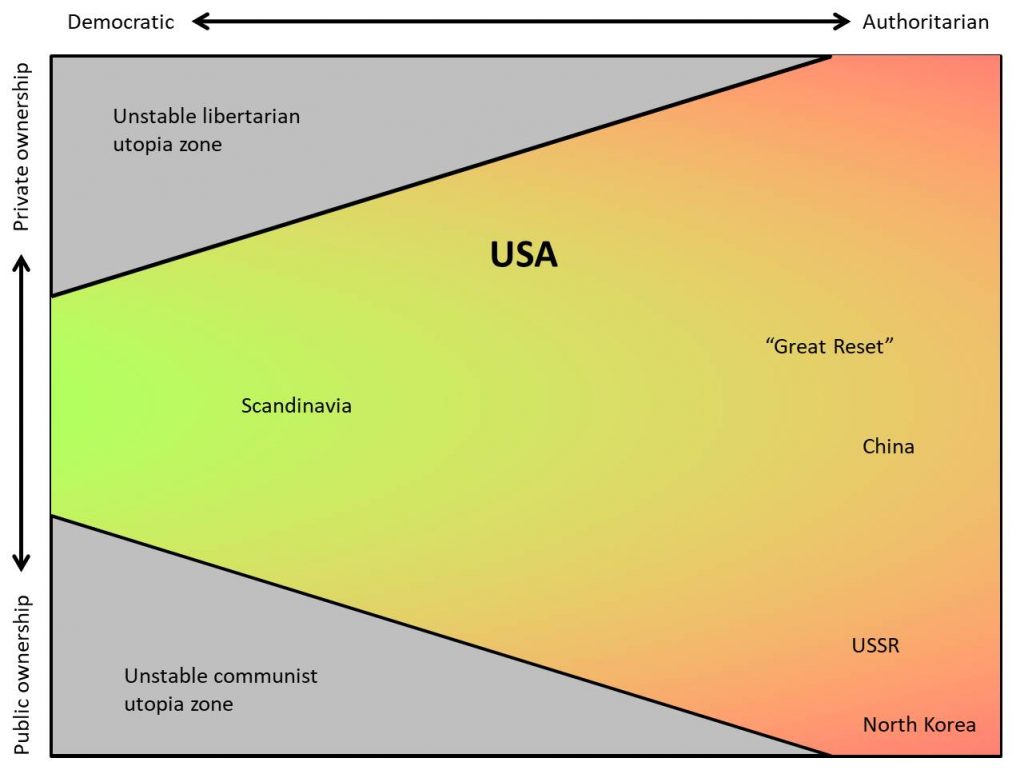

I have attempted to place various nations onto the plane of political possibility. While I’m fairly confident about where the United States of America is at presently, I don’t have first-hand experience of other nations and so may be making assumptions based on media bias. Feel free to let me know if you feel your country is misplaced here.

On the horizontal axis, the United States is currently in between democracy and authoritarianism. It is also moving in the direction of authoritarianism, which I will address in the next chapter. In theory, we have a representative democracy with checks and balances, in which the right of participation has been expanded over time from a privileged subset of the population to all citizens. In practice, this remains true only at the local level. At higher levels it has become virtually impossible to get on the ballot and to obtain fair treatment in the media without the endorsement and support of entrenched unelected power structures – what might be called the military-industrial-medical-pharmaceutical-technological-educational complex, or something like that.

On the vertical axis, the US is out of balance in the private-ownership direction. We still have functional public utilities and a concept of public goods, but we also have privatized sectors of the economy that objectively function better when managed as public utilities. Perhaps the best example of this is our medical system, which leaves millions of people without affordable access to essential care, while collectively costing us more than twice as much as in comparable nations with public health care, with inferior outcomes in terms of population health and life expectancy.

Increasingly we are seeing calls for a “Great Reset” of the world economy, accompanied by flowery language about addressing climate change, investing in our future, and improving our lives. What is notably missing from this grand vision is any mention of democracy. It is entirely the product of extremely wealthy influencers like the World Economic Forum who wish to believe that they can save the planet while maintaining their privilege and creating happy lives for the peasants in a world with no privacy and a much-reduced concept of personal property.

The peasants, of course, don’t get much say in this, and those who don’t look forward to this sort of nouveau urban digital feudalism are viewed with a mixture of disdain and pity. We have so far seen disastrous results from handing the reins of government to those who seek profit and self-enrichment, and it is difficult to imagine that an authoritarian Great Reset will truly benefit anyone outside the circles of privilege that are promoting it.

On the right-hand side of the spectrum, the vertical axis becomes far less important. Once a small and unelected group of people gains complete control over government, it doesn’t matter that much from the perspective of the common folk whether that group of people is ideologically communist or ideologically capitalist. The effect, in terms of decisions that benefit the ruling class at the expense of those outside of it, is inevitable under all forms of authoritarianism.

Many volumes have been written about political theory, seeking to make the case that one particular structure of society is preferable above all others. As for myself, I would much prefer to inhabit a world in which every citizen has a voice, and in which we have a balance of public ownership and private enterprise. In Part 11, I will examine what might be necessary to arrest our current movement away from that ideal, and how we might begin to reclaim our representative democracy.