This year will not be remembered primarily for its weather in most parts of the world.

That said, 2020 did bring a record-breaking hurricane season and a continuation of worldwide weather extremes that are almost certainly linked to climate change.

Here in western Oregon, we mostly saw a continuation of the protective bubble that has been over us for the past few years, with muted headlines and no major floods, storms, heat waves, or cold snaps. The one notable exception arrived late on September 7 and continued for the next 48 hours. Interrupting a month of late-summer sunshine with warm days and gentle winds, a cold and dry airmass came barreling down from the Canadian tundra, generating unprecedented northeasterly winds and single-digit humidities. Had this happened in October – when such events are more common – crews would have simply spent a few days cleaning up fallen trees and restoring power to outlying areas. But ahead of the first fall rains and following on weeks of dry heat, the winds proved catastrophic, fanning existing small fires to hundreds of thousands of acres overnight and igniting many new ones from sparking power lines. Four unstoppable conflagrations raced down the valleys of the Clackamas, North Santiam, McKenzie, and North Umpqua rivers, obliterating small towns and placing most of the eastern Willamette Valley on some level of evacuation notice until the winds died down.

Farther west, away from the fire threat, the easterly winds carried vast plumes of smoke over the Pacific, first dropping ash under ominous orange skies and later leaving the valley in a cool gray stagnant smog, thick enough to block summer sunshine and create winter-like inversion conditions and ongoing hazardous air quality. At its thickest, the smoke knocked nearly 30 degrees off of daytime temperatures, generating a strange and short-lived dystopian November in between summer and fall. Blessed rain arrived in quantity on September 18, clearing the air, mostly extinguishing the fires, and putting an end to the 11-day pyrogenous climatic aberration. Those in California would not be so lucky; their historic fire season began months earlier and their rains would not arrive until much later.

Temperature trends

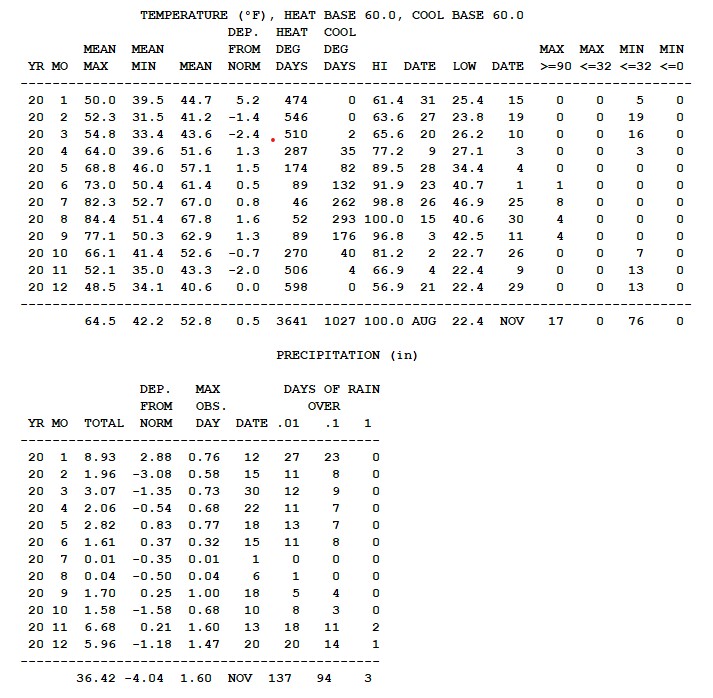

The year’s highest temperature – exactly 100.0ºF at our place – arrived without much fanfare on August 15: a one day blip with a couple of 90-degree days on either side. With seventeen days above 90º, the summer was substantially warmer than mild 2019 but on par with other recent years. The coldest temperature of 22.4º was also reached without much notice on both November 9 and December 29, though the low of 22.7º on October 26 flirted with earliest-coldest records and brought a resounding close to a long growing season. The entire year remained within this 77.6º range, somewhat remarkable considering that some individual summer days covered nearly 2/3 of that distance between morning and afternoon. We had no real intrusions of arctic air; low 20s are about the limit of normal dry winter days absent advection of colder airmasses from the northeast. With no arctic air, we also had no snow to speak of; only a few flurries from the coldest late-winter showers. We did have a total of 76 days with lows below freezing – the same number as 2019 but well above recent averages. This reflects a recent trend – perhaps exacerbated by climate change – of a greater proportion of clear fall and winter days with frosty mornings and comparatively fewer days of clouds and rain. Overall, the year averaged 0.5 degrees above long-term averages – in keeping with the previous three years that have been unremarkable in their temperature normalcy.

Precipitation trends

The Willamette Valley was in drought status for all of 2020, at times and in places listed as severe, after inheriting a significant shortfall from October-December 2019. This was an odd sort of hydrologic drought: more a result of long-term shortages than short-term patterns and so with limited effects on farmers and gardeners. Total rainfall for 2020, at 36.42”, came in at 90% of normal – higher than 2018 and 2019 but not yet enough to break the longer-term drought. With periods of dry clear weather seemingly becoming the wintertime norm, it is becoming more important to win the atmospheric river lottery; to end up beneath those stationary bands of intense rainfall dropping inches at a time and bringing us closer to our precipitation quota. More often than not in 2020 those bands took aim at western Washington, but deluges from November 13-18 and December 16-21 put dents in the hydrologic deficit. As I write this, the near- and long-term winter forecasts look moist, with a La Niña pattern directing the dominant storm track toward the Pacific Northwest. With luck this will be enough to end our drought status moving into the 2021 growing season, with snowpack, streamflows, and aquifers recharged.

Monthly notes

Januarywas an exceptionally wet and dreary month, even by Oregon standards. Flooding rains stayed to the north, and we never received more than 0.76” on any one day, but rain fell on 27 of the month’s 31 days as we were locked in an onshore flow pattern with a continuous parade of Pacific fronts. The monthly total of 8.93” was the highest of the year, but coming on the heels of a dry fall and followed by a dry February through April it was not enough to offset the year’s overall droughtiness. January averaged 5.2 degrees above normal – the year’s largest departure thanks to the monthlong pattern of warm-ish clouds and rain.

February saw a switch to unseasonable sunshine, with rain on only 11 of 29 days totaling 1.96”, or 39% of average. The remaining days brought frosty mornings and sunny afternoons, exceeding 60 degrees by the end of the month despite a below-normal monthly mean.

March brought a continuation of the same mostly-dry, mostly-sunny pattern up until the equinox, when the pattern finally shifted to cool and wet. That was too late to make up for a monthly rainfall deficit (3.07”, or 69% of normal), and the continued frosty mornings led to a -2.4º temperature departure for the month despite a feeling of late winter warmth.

The brief cool-and-wet interlude ended April 5, ushering in an above-normal, mostly-sunny month of 60s and even low 70s for daily highs. A low of 27.1 on the 3rd gave orchardists heartburn – though in general temperatures did not drop as low as feared and blossoms and young fruits were spared. The 14th brought the season’s last frost at 31.1º, and drying conditions allowed farmers and gardeners to get crops in on schedule. The beautiful spring weather was largely overshadowed by the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated statewide shutdown that even included closures of beaches and outdoor recreation.

May brought above-average precipitation, much-needed but not exactly welcomed by those wishing to till and plant. Dry windows from the 7th-11th and 24th-29th brought highs in the 80s and an early taste of summer, though some days in the mid-month wet spell struggled to reach 60 degrees, keeping bees in their hives and putting a damper on dreams of a bumper honey crop.

June had rain on every day from the 6th through the 16th, largely washing out blackberry blossom nectar at peak bloom and leading to an anomalous beekeeping year in which the early-season bigleaf maple honey was a large proportion of the harvest. The rain only totaled 1.61”, slightly above normal but enough to delay the onset of summer drought and prolong blooms and green lawns.

After a sprinkle on the first day for 0.01” July was completely rain-free with warming temperatures. The first third of the month had highs in the 70s, then mostly 80s in mid-month with five days in the 90s at month’s end.

August can be hot and sticky but not this year, with highs around 85º on most days and only a brief and mild mid-month heat wave topping out at exactly 100º on the 15th. One brief shower – 0.04” on the 6th – provided minimal disruption to drying grains and seed crops.

September started out in the 90s with more of the same in the forecast, but the smoke beginning on the 8th dimmed the sun sufficiently to lower daytime highs by over 20 degrees. The respite from the heat made it easier to stay indoors out of the smoke, though clean air became a relative term as ash seeped in around doors and windows. Were it not for the fires the month would have been historically warm; as it was September finished slightly above average. After an inch of fire-quenching rain on the 18th, additional rains after the equinox brought the monthly total above average and paved the way for an early fall re-greening.

Aside from rain on the 9th-14th, October was mostly dry, continuing the pattern from the previous two years and a boon for late seed harvests delayed by the days of smoke. Total rainfall at 1.58” was just 50% of normal. After no frost threats through September and mid-month, a killing frost on the 22nd was followed by a low of 22.7º on the 26th, ensuring that even tarp-covered tomatoes and peppers grew no more. As a gardener I must say I prefer to have a clear end to the season, as opposed to those years where we harvest increasingly flavorless peppers until Thanksgiving.

We managed to – just barely – exceed normal rainfall in November – thanks to a mid-month atmospheric river. With dry soils and low streamflows, this rain didn’t cause the flooding concerns that a similar event would create later in the season. Overall the month brought a wide variety of weather – warm sun at the beginning, warm rain, cold frosty mornings, a rare sunny Thanksgiving, and finally some cold inversion fog, and averaged a bit below normal temperature-wise.

Early December often brings the year’s coldest temperatures in a dry spell; the dry spell arrived on schedule in 2020 but not the cold, with highs reaching over 55º and lows only around 25º. Mid-month through the solstice brought another atmospheric river, followed by occasional rain through month’s end but not enough to reach the 7.14” average for the wettest month of the year. After a foggy and rainy Christmas, bright sunshine on the 27th and 28th brought hope for longer days ahead and brighter times in 2021.