I’ve written a fair bit here about the Covid-19 vaccines, starting with my initial concerns – based on the nature of the vaccine technology and the history of coronavirus vaccine attempts – that they would be neither safe nor effective. As it stands today, it’s clear to everyone that they aren’t particularly effective. The official narrative still claims that they are safe, although the VAERS database and thousands of seriously injured people would beg to differ, and I increasingly expect that they will be viewed as an unmitigated disaster through the lens of history.

Here we are two years later with another new virus spreading around the world, and another set of vaccines being rolled out to combat it. It’s still uncertain whether monkeypox spread will reach the point that mass vaccination is encouraged, but given that the rise in case counts shows no signs of stopping I decided that it was time for me to learn more about these vaccines to form an opinion about them. I have to say that I was pleasantly surprised to encounter very few red flags. If monkeypox spreads to the point that a personal encounter with it seems likely, I would personally be willing to get either of the two available vaccines – though ideally I would like to wait until we have more data with regard to real-world effectiveness against monkeypox which should be forthcoming in the months ahead.

The Vaccines

The available monkeypox vaccines were developed as smallpox vaccines after the eradication of smallpox – primarily as a precaution against potential bioterrorist smallpox release. There are two available in the US; other versions are available worldwide but all approved to date are of the same two general types.

The ACAM2000 vaccine is a live-Vaccinia-virus preparation injected through the skin, containing 250,000-1.2 million viral particles, that initiates a local Vaccinia infection which generates a pustule and an eventual scar. The immune response generated against the Vaccinia virus is also effective against smallpox and monkeypox. It is nearly identical to the previous smallpox vaccine received by many older adults, except that it has lower genetic diversity (being derived from a single clone of virus) and it is grown in culture in cells derived from monkey kidneys rather than on the skin of calves as in the older version. As it contains a replicating virus, it can potentially spread from the injection site to other people or other locations, it can cause severe illness in immunocompromised people, and it has a higher rate of acute adverse reactions than many other vaccines. The USA has a stockpile of around 100 million doses of this vaccine as a primary defense against a smallpox attack.

The Jynneos or Imvamune vaccine is a live-attenuated-Vaccinia virus preparation administered similarly in two doses each containing 50 million-400 million viral particles. These viruses are capable of infecting cells and hijacking them to produce viral proteins (so that cells know they are infected and send the appropriate immune signals), but they contain mutations rendering them unable to complete the process of forming complete new viruses and are therefore unable to replicate. The viruses are grown in cells derived from chicken embryos (in which they *can* replicate). It has a lower rate of adverse reactions and appears to generate a similar or even immune response, as measured by antibody titers. This vaccine was developed with the intent of offering it to immunocompromised and otherwise at-risk individuals in the event of a smallpox attack. The USA once had a stockpile of over 20 million doses but these have since expired, and it is currently in limited supply.

The Good

It’s old technology

While the Covid-19 vaccines represent the latest whiz-bang vaccine technology borne of modern molecular genetics, never before deployed on a wide scale, the monkeypox vaccines represent the oldest known vaccine technology – the work of Edward Jenner in the late 1790s – which has changed surprisingly little since that time.

Pardon my foray into history, as this is a most interesting story.

The oldest intervention to stimulate immunity was called variolation – dating back to the 15th century – which utilized old smallpox scabs to induce a milder case of smallpox than would typically be acquired naturally. The practice worked but carried a risk of death from smallpox in the range of 1-2%.

In the 1700s it was noticed that milkmaids – who occasionally got cowpox blisters on their hands – did not contract smallpox. Edward Jenner was certainly not the first to apply this principle, but he did prove it to the satisfaction of the scientific community and give it the name – from Latinvaccinae: “of the cow” – that persists to this day and that has been questionably applied to the genetic transfections employed against Covid-19.

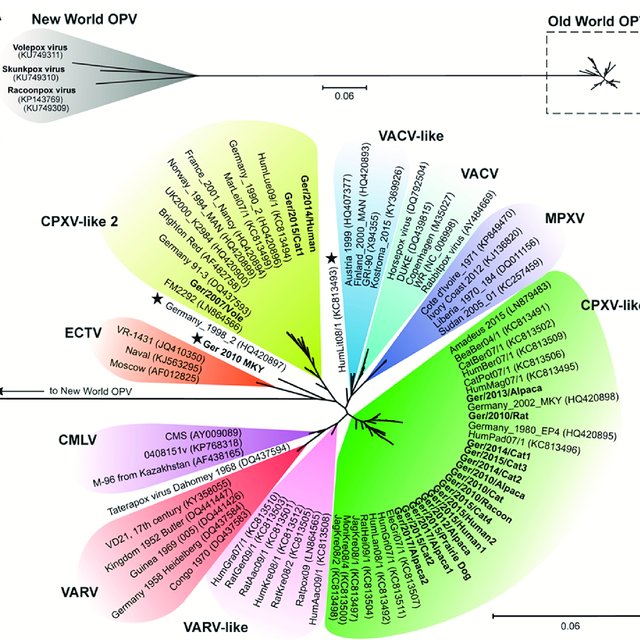

Orthopox viruses are relatively large (~3x the diameter or ~30x the volume of SARS-CoV2) containing a comparably large DNA genome (190,000 nucleotides or 6x the size of SARS-CoV2) that mutates rather slowly. These viruses have coevolved with mammals, and there is one specialized to a great many species – cowpox, horsepox, monkeypox, camelpox, raccoonpox, volepox, etc. Smallpox was the human-specialized version. It so happens that some of the other orthopoxes can also infect humans but cause mild infections, rarely transmit between humans, and generate cross-reactive immunity against smallpox.

Although the initial smallpox vaccinations utilized cowpox, modern science revealed that the virus being cultured for vaccines in the 20th century was not actually the same virus as was infecting cattle and that it was most closely related to horsepox. Having been cultured for a couple of centuries it was no longer identical to any wild virus, and it was named Vaccinia.

From the tree above, it is apparent that monkeypox viruses (MPXV, dark blue) are more closely related to Vaccinia-group viruses (VACV, blue-green) than to Variola/smallpox viruses (VARV, red). Thus it is not surprising that if Vaccinia infection protects against smallpox, it also protects against monkeypox. And indeed this has been borne out by trials against monkeypox in monkeys. (There has never previously been enough monkeypox in humans to do a trial, creating some uncertainty which I will discuss below.)

In any case, these are not novel vaccines for a novel virus, as was the case with Covid-19. Widespread transmission of monkeypox among humans is novel and quite concerning, but it happens to be a virus against which our oldest and most time-tested vaccine is likely to be effective.

We have been poking people with Vaccinia-virus vaccines on a large scale since the early 1800s – in many times and places approaching 100% of the population. This has known risks, as I will discuss below, but at this point it has very few unknown risks. The minor differences between the current-generation vaccines and the original versions seem unlikely to introduce any new risks – although sometimes there are indeed devils in details and there is always some nonzero possibility that a small mutation in the virus might increase the odds of autoimmunity or create a toxic protein.

They are fully tested and approved

Both of the available vaccines were developed over decades and safety tested in humans in multiple clinical trials over a period of 10+ years. There was no pandemic rush or “Operation Warp Speed” to cut corners and ignore worrying safety signals. ACAM2000 was FDA approved in 2007 for anyone over one year of age. Imvamune was FDA approved in in 2019 (2013 in Europe) for anyone over 18 years of age. The current Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Imvamune is not for the vaccine itself but for use in children and for intradermal injection which is supposed to allow for smaller doses to make the existing supply stretch further. Intradermal injection should not be a safety concern but it could impact efficacy as the practice is based on limited research.

Monkeypox should respond to vaccination

During the development and rollout of Covid-19 vaccines it was often noted – at least outside the mainstream narrative bubble – that no one had yet produced a viable vaccine against a coronavirus. The small RNA viruses in this family mutate rapidly, rendering vaccine antibodies less useful, and they even have a tendency to exploit antibodies to infect new tissues in a phenomenon known as Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE). In contrast, vaccination against orthopox-family viruses has a long history of success, and given that the Vaccinia vaccines are effective against monkeypox in monkeys, it is reasonable to assume they will also be effective in humans. Not 100% guaranteed, but a reasonable assumption. Based on our experience with the closely-related smallpox, it is also unlikely that immunity will wane rapidly or that the virus will rapidly mutate to evade vaccination.

The Not-So-Good

Mass vaccination will cause some illness and some death

That’s not a statement of speculation. Based on the known adverse effect profiles of older smallpox vaccines when they were in widespread use, myocarditis occurred in 1 out of 175 people and death in 1 out of 2 million. The attenuated-virus versions appear to be safer, but they haven’t been injected into enough people yet to identify the rate of very rare complications.

That’s a known risk I can live with, and preferable to getting monkeypox, but it does mean that the preferred outcome of the next few years is not that everyone gets vaccinated but rather that monkeypox gets contained before that becomes necessary.

Compared to the initial covid response and quarantine, I’ve been a bit surprised by the rather laissez-faire approach of public health authorities to controlling the spread of monkeypox. To the extent that quarantine, contact tracing, and isolation might actually be useful at this point, it seems worth trying to a greater degree than is currently happening.

If it reaches a point at which community transmission is widespread, I most certainly do not support imposition of the sort of lockdown and life-disrupting measures that were put in place for Covid-19. I would much prefer to receive one of these vaccines than to change my behavior and put my life on hold in an attempt to avoid infection.

Effectiveness against monkeypox in humans remains unknown

Smallpox vaccines are crudely estimated to be 85% effective against monkeypox infection. The absence of a solid number here is due to the fact that prior to 2022 no human monkeypox outbreak led to more than 1,000 infections. So this number is effectively a guess based on immunogenicity, trials in monkeys, and a limited observational study of humans during small monkeypox outbreaks in the 1980s.

The good news is that at current rates of infection and vaccination we should soon have better estimates of how effective these vaccines really are.

Side effects overlap with those of Covid-19 and Covid-19 vaccines

It’s a bit troubling that these vaccines, especially ACAM2000, can cause myocarditis of all things. We already know that this condition can arise as a result of Covid-19 vaccination, and it appears that subclinical heart inflammation may be relatively common. Covid-19 infection is also known to cause cardiovascular complications, and the spike protein – however introduced into the body – appears to trigger clotting. All of this means that the rate of myocarditis in the present environment might turn out to be higher than the 1 in 175 observed in the clinical trials, or perhaps monkeypox vaccination will add to a cumulative burden on the heart in those who have been vaccinated and infected multiple times. As someone who has not been vaccinated against Covid-19 and who has experienced one mild infection, I am not personally too worried about this.

We could be vaccinating into a pandemic again

Geert Vanden Bossche has been the most vocal voice warning that vaccinating against Covid-19 in the context of high infection rates will give the virus ample opportunities to mutate to evade and even capitalize on vaccine-produced antibodies.

We may face a similar situation with monkeypox. This is especially true in the case of “post-exposure prophylaxis.” The incubation period of monkeypox is typically longer than the time required to generate antibodies following vaccination, which means that vaccination immediately after exposure can prevent infection or reduce disease severity. This also means, however, that the monkeypox virus will be replicating at the same time that the body is developing an antibody response, which creates an environment favorable to immune escape mutation if it is done on a wide enough scale.

It may be that the mutation rate of monkeypox is low enough that this isn’t really a concern, and it is also true that however the virus evolves in the future we will have no way of knowing whether our vaccination effort played a role. So…while this is a concern, there is no clear action to be motivated by it except perhaps to avoid disease exposure during the vaccination period.

What Does All This Mean?

I still feel wounded by the coercive messaging and ostracizing mob mentality surrounding the Covid-19 vaccines. I am increasingly convinced that my decision not to receive those vaccines was the right choice for me, and I remain concerned that we have only seen (or at least publicly acknowledged) the tip of the iceberg in terms of adverse effects.

I am also deeply skeptical of the continual addition of new vaccines to the childhood schedule with no in aggregate testing, and I suspect that over-vaccination during immune system development is likely to be playing a major role in the epidemic of allergies and autoimmune-linked conditions in young people.

That said, I have no problem with the general principle of vaccination, especially inasmuch as it was empirically developed prior to the political dominance of the pharmaceutical industry and the hubris of the modern secular religion of Progress (or Science). So the fact that these vaccines use very old technology actually gives me greater confidence in their probable safety and efficacy.

I still stand firmly opposed to any and all mandatory vaccination by government decree, my willingness to compromise on this in particular situations having been destroyed by my government’s willingness to mandate an entirely novel, inadequately tested, emergency-authorized vaccine against a pathogen with fatality rate of well below 1%.

That said, having done my research, if monkeypox continues to spread and to hone its ability to infect humans – quite possibly becoming more virulent in the process – I will not hesitate to receive one of these vaccines with the aim of avoiding what appears to be a most unpleasant disease.