Toward a More Equal America, Part 7

In Part 6, I highlighted voices from the Black and transgender communities which are critical of mainstream social justice. These voices point out that social justice activism is rich in demands for emotional work, attitude adjustments, minor policy changes, and opportunities for a select few representatives from marginalized groups to join the comfortable classes; and yet notably deficient in demands for the sorts of structural economic reforms that would be necessary to meaningfully improve the lives of a majority of Black or transgender people. It’s nice if the cops won’t kill you, in other words, but that provides slim solace if it remains impossible to earn a living wage, afford food and housing, and escape a life of petty crime in the name of survival. Because mainstream social justice represents no threat to the neoliberal agenda, these voices argue, it actually helps to perpetuate neoliberalism.

In this essay I return to my own voice. Before I begin, I would encourage everyone to read On Gaslighting, by Nora Samaran. For anyone unfamiliar with the term “gaslighting” or with the idea of unintentional-but-still-harmful gaslighting, I quote her opening paragraphs:

I keep having the same conversation over and over.

That thing where someone undermines your perception of reality, and says you’re crazy, or denies that something is happening that is in fact happening?

When people we love and trust do that to us? It really messes with our minds.Over time, or when it is about important things, this experience of having words deny reality can fundamentally shatter our sense of self-trust and our ability to navigate reality.

“There’s a word for that,” I say, hearing yet another such story from a female friend. “It’s gaslighting.”

Friend says “What’s gaslighting? I’ve never heard of that.”

“It’s when someone undermines your trust in your own perceptions and you feel crazy because your instincts and intuition and sometimes even plain old perceptions are telling you one thing, and words from someone you trust are telling you something different.”

“Oh.” (looks it up).

“Oh,” friend says again, reading. “But gaslighting seems to mean when someone does that to you intentionally. I don’t think he was doing it to me intentionally. Actually, it’s even harder to pin down because I don’t even think he was fully aware he was doing it and he got upset when I talked about it. But he was. And it makes me question my sanity.”

Do you understand the depth of the harm of making someone question their sanity? This is serious shit. This is not like “whoops I brought you the strawberry ice cream and forgot you like banana better.” It is poking a hole in someone’s fundamental capacity to engage with reality. Understand it in a context in which women have been being told every day for their entire lives that their perceptions cannot be trusted – when in fact our perceptions are often bang fucking on – and you have a systemic, pervasive, deeply psychologically harmful phenomenon, insanity by a thousand cuts.

Nora Samaran, “On Gaslighting

I believe that neoliberalism is using a social justice narrative to gaslight the entire United States, and much of the world.

The nature of this gaslighting is as follows. Social justice paints a national narrative of progress toward greater equality, beginning with the original sins of slavery and colonization and proceeding through abolition, women’s suffrage, civil rights, gay marriage, transgender equality, and the ongoing (and likely to be successful) Black Lives Matter protests against militarized and racist police practices. This is in direct conflict with the lived experiences of a majority of Americans, who – as I discussed in Parts 1 and 2 of this series – have found themselves squeezed between stagnant wages, skyrocketing costs of living, and a profound absence of respect or empathy from those in positions of power, and have logically concluded that equality is decreasing.

To counter such claims, neoliberal social justice offers one of three answers:

- Your experience is not real (because statistics show that America is more equal than it was in the past).

- If you are white and male, your perceived suffering is actually just an overdue pruning of your unearned white male privilege, so deal with it.

- If you are anything other than white and male, your suffering is due to the white supremacist patriarchy, and the solution is to continue the work of social justice.

Most people on the losing end of neoliberal economics don’t find these answers very satisfying. For one thing, if equality is improving over time while lived experience of quality of life is declining, it’s difficult to argue that remaining inequality is the cause of that decline. For another, most of these people have direct experiences of oppression that, according to the logic of social justice, does not and can not exist.

The result of prolonged gaslighting, as Samaran clearly describes, is a loss of sanity, and I would posit that this national insanity is at least partially responsible for the election of Donald Trump, a narcissistic and divisive man with little talent for leadership who rose to power by giving voice to the simmering anger of millions of gaslit, downtrodden Americans.

The mechanism of this gaslighting remained a mystery to me until recently. The people involved in social justice work – from authors and activists to my own friends and acquaintances – all seemed to be good people with honest and moral intentions of changing the world for the better, of being better ancestors to their own children and the children of the world. When I delved deeper into the work of rooting out implicit bias and understanding privilege, I could find little that I would disagree with. At the same time, I felt strongly that something was amiss, that the ideology of social justice could not explain many of the inequalities I observed in the world and that it was actually serving to distract attention from them. Finally, I came to a realization: what if the framework of social justice was not wrong, but rather incomplete?

High on the recommended reading list for white people during the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests is Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor by Layla F. Saad. In this book – intended as a guide for journaling and reflection – Saad, a Black woman, describes the many ways in which a culture of white supremacy is oppressive to people of color, and encourages readers to reflect on their own attitudes, biases, and behaviors in this regard.

I had an interesting experience working through it, because I discovered that aside from a fear of encountering Black men on dark urban streets gleaned from too many childhood 10 o’clock news crime reports, I could not identify much in the way of deep-seated racial biases within myself – which I attribute to primarily inhabiting racially homogeneous (mostly white) communities in which race did not serve as a major point of distinction. I did, however, reflect more broadly on her journaling prompts. How have you felt superior to others? she asks in the context of race. How has that feeling led you to act in ways that are harmful to others, or to fail to intervene when you observed others committing harm?

It turns out, upon self-reflection, that I have felt superior to others. I have acted in ways that privileged myself at others’ expense, I have been on the losing end of oppressive attitudes and behaviors, and I have observed similar behaviors in others. And yet somehow very little of the oppression that I have perpetrated, experienced, or observed fits neatly into racism, misogyny, or any of the other categories of social justice. At first I doubted whether it was therefore of any importance whatsoever, but then a little alarm bell went off in my head. Remember gaslighting? That essay I read telling me to trust my own intuitions, reflections, and perceptions even when “experts” that I trust are telling a different story? Might that be going on here?

We are all familiar with the intersecting identities that form the axes of oppression in social justice theory:

- Gender (male/female and cis/trans/nonbinary)

- Race

- Sexual orientation

- Religion

- Ethnicity

- Disability status

- Age

- and a few others.

If we define oppression in the same way that Saad defines racism – prejudice in the context of a difference in power – then we must ask: why must oppression occur only in the context of identity? Might other axes of oppression exist, and if so is there any ethical reason not to include them within the framework of social justice? Might these “invisible” axes of oppression help to explain how neoliberal social justice is gaslighting America, telling a story that is in conflict with citizens’ lived experience?

Invisible Axes of Oppression

Based upon self-reflection on oppression I have observed or experienced in my own life, I posit that there are at least six important intersecting non-identitarian axes of oppression in American society, all of which are fully deserving of social justice activism.

These are:

- Occupation

- Education

- Family status

- Class

- Intelligence (mathematical/analytical)

- Origin (native to an area vs. immigrant)

I will discuss each of these in turn, based upon my own experiences and observations. Within each one, I will attempt to identify the nature of the power difference, the parties involved (who is oppressing, who is being oppressed), and the method by which oppression is occurring.

Occupation

I have very few working class friends. That number might even be zero, but it depends on how exactly the distinction is defined. I have friends who earn minimum wage or slightly above, but I do not consider them working class for reasons I will explain below. This is a problem, I suggest, because it highlights one of the greatest divides in American society – at least on par with race in terms of significance.

For me, this divide dates all the way back to the beginning of high school. In Me and White Supremacy, Saad discusses the way subtle racism leads to black kids sitting together in the cafeteria, away from the white kids. We had only one black kid in our small town school, and from my viewpoint at least he was reasonably well accepted, so that wasn’t the divide that I observed. Instead, from about ninth grade onwards, we had college-bound kids and work-bound kids: those who were studying advanced math and literature in order to get a high SAT score, and those who were taking shop and welding classes and planning to carry on the family business or find work around town after graduation.

The divide itself is not a problem. The problem is that we (and I say this as one of the college-bound kids) did not respect them. We weren’t especially mean to them, but we considered ourselves better, and – in a graduating class of 61 students – I can sadly say I remember the names of all of my college-bound classmates, but few of the rest. We were taught this disrespect by our families – most of whom were themselves college-educated. We were told that we ought to work hard in school, or we might end up flipping burgers – as if flipping burgers were a worthless occupation and not a meaningful contribution to society.

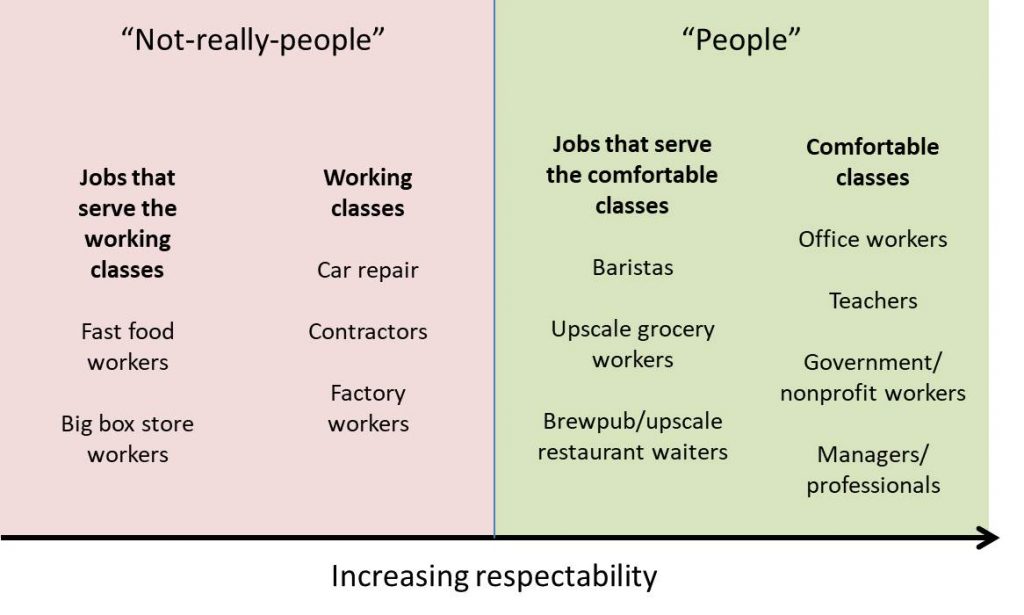

When I discuss oppression based on occupation, I am referring not specifically to rate of pay or type of work, but whether the work – and thereby the person doing the work – is respected by members of the financially comfortable, educated classes in society. From the perspective of the comfortable classes, respectability of work in current American society looks something like this:

From the perspective of the comfortable classes, i.e. the privileged people along this axis of oppression:

- Other members of the comfortable classes are people worthy of respect.

- People working service jobs that serve the comfortable classes are also people worthy of respect, albeit slightly less. These are considered acceptable jobs for young adults born into the comfortable classes, as they apply for better jobs or make plans to pursue further education. The comfortable classes interact with these folks in a friendly manner, leave generous tips, and occasionally offer suggestions as to how to move up in the world. These jobs act as a relief valve to accommodate the fact that there are more children of comfortable-class people graduating from college than there are available jobs in the comfortable classes, and they save the comfortable classes from actually having to interact with working-class people on a regular basis. Younger people in these jobs – who are seen as using it as a stepping stone – are treated with more respect than elders for whom it is a career.

- Members of the skilled working classes are respected for their labor alone, not for their humanity. We might talk about having a good mechanic or a good electrician, but chances are they are not our friends and we do not really value them as people. If we have a few friends and family in these roles, we consider them a bit odd but honor them for “following their own path.”

- People working “unskilled” service jobs – in call centers, as big box cashiers, or as fast food workers – are seldom regarded as people at all. We treat them like machines, and if they make a mistake we inform them rudely and expect contrition. Chances are we have no personal relationships whatsoever with people working these jobs, and if we do have a friend or family member in these roles we consider it a tragedy in need of correction.

This occupation-based dehumanization parallels and perpetuates the neoliberal commodification and devaluation of human labor. There was a time – 40+ years ago – when most of the unskilled service jobs did not yet exist (no Amazon warehouses, no nationwide Walmarts) and when the skilled working-class jobs were mostly unionized and commanded respect and a living wage. That this change should be completely ignored by social justice efforts is a reflection of the fact that social justice ideology is a product of colleges and universities, which themselves are occupied by present and aspiring members of the comfortable classes. The fact that the comfortable classes do not regard the working classes as worthy of respect allows us to ignore wage stagnation, benefit cuts, rent increases, and all of the other trends that are making survival increasingly tenuous for this segment of the population.

Education

We do not wear our education credentials on our sleeves; oppression based on education occurs primarily at the level of hiring, and in particular in the vast number of job applications that require a generic college degree. Just as I argued in Part 3 that the only ethical function of an economy is to facilitate exchange of goods and services, I would argue that the only ethical function of higher education is to provide necessary preparation for a career. I would further argue that there is no job or career for which an adequate apprenticeship and passage of any necessary certification exams cannot substitute for a formal education.

Thus I find it ironic that so many job descriptions have a nondiscrimination clause directly adjacent to a requirement for a college degree. The job announcement always spells out exactly the skills and experience required. If an applicant can demonstrate that they meet those requirements, they should be hired. Requiring a degree only ensures that the applicant had enough resources to pay for college or a good enough family credit score to secure college loans.

Having been through four years of college at a well-regarded liberal arts institution, I can attest that it was a positive experience and a good preparation for graduate school, but in no way necessary to perform any of the degree-requiring jobs that I did after graduating. The near-universal requirement of college degrees for well-paying jobs with benefits thus represents a form of discrimination. It is a statement that the employer would prefer to hire someone from the comfortable classes, and that fully capable working-class applicants – for whom college was not financially a viable option – need not apply. Education-based oppression therefore directly serves the interests of class segregation and neoliberalism.

Family Status

Growing up in a small town, I quickly learned that some families had status. Typically that meant that they had wealth, but it also meant that they had history – members on the city council, farms or family businesses dating back three or four generations. My family was at the bottom of the status pile. My parents were never married and separated (this matters in a Christian community), my father was not raised in the community, and he had no wealth or business to his name. I cemented my lack of status in high school by ratting out a high-status basketball player for cheating on an exam, resulting in his suspension from sports for a few games and bringing shame to his family. I managed to partially overcome my lack of status through intelligence – see below – but my lack of status in my community was central to my decision to leave town after high school.

Status confers access to social capital that brings opportunities for success and career advancement, providing unearned privilege to some children in a manner analogous to inherited wealth. Status is as old as human civilization, nearly impossible to address politically, and not uniquely neoliberal in any way. Even so, it is worthy of mention as an axis of oppression that serves to perpetuate inequality, and a potential target for social justice activism.

Class

I have already used the word “class” in the context of “working class” and “comfortable classes” to describe groups of people. In describing class as an axis of oppression, I am referring to all of the subtle and not-so-subtle indicators that we belong to one or the other of these tribes. These include word choice, patterns of speech, demeanor, clothing choices, and even our given names. It has been proven that job applicants with traditionally Black names are interviewed at a lower rate by white hiring boards. Though I’m not aware of any parallel study, I would wager that the same would be true if we compared traditionally working-class names (e.g. Tanner, Dakota) with traditionally upper-class names (e.g. Joseph, Christopher).

Classism makes it difficult for working-class people to succeed in comfortable-class spaces like colleges because they perceive – usually quite correctly – that they are being judged negatively. It adds one more barrier to upward mobility; even if a person is able to “escape” the working classes by possessing high intelligence (see below), attending college, and landing a comfortable-class job, it can remain difficult to fit in and feel comfortable.

Class discrimination is insidious, continuous, unconscious, and structural. In confronting it we will need to use all of the tools developed to confront racism: understanding implicit bias, identifying microaggressions, avoiding tokenism, saviorism, etc. Given that people of color make up a significant proportion of the working classes, there is a substantial overlap between racism and classism in the United States, and I would even go so far as to hypothesize that – in regions where the comfortable classes are predominantly white and the lower classes are predominantly people of color – some of what appears as racism may actually be classism in disguise. That is to say that if we were able to determine what was going on in the minds of people when discriminating based on race, it might be less “person of color = not worthy of respect” and more “person of color = working class = not worthy of respect.” That doesn’t make it any less impactful to those affected, of course, but it may alter the nature of the activism required to effect change.

Intelligence

Modern society privileges a certain variety of mathematical, analytical intelligence of the sort that can ace the SAT exam. This is far from the only variety of human intelligence; some people have linguistic, musical, artistic, literary, emotional, or social genius, to name a few, and all are valuable to a flourishing human community. But mathematical/analytical intelligence is useful for the sorts of jobs that oversee a global, technological economy, and so it has been granted special status among the comfortable classes.

This happens to be the way that my brain works, and it was my ticket to success all through my years of education. It also constitutes unearned privilege. I did not construct my brain. Too often I watched others work twice as hard to receive lower grades and thought “I am a winner!” School became a competition, with top marks as validation that I was worthy of respect.

I don’t want to get too far off into the weeds here, but I will say that when I reflect on the ways in which my privilege has caused harm to others, this is an axis of oppression that comes to mind. I seem to have developed some bad habits, in terms of using my intelligence to gain respect rather than to teach and empower others. I have noticed that those who are closest to me seem to become less confident in their own analytical intelligence over time. I feel I am at least partly responsible. My tendency is to identify problems before others recognize them, devise and implement a solution, and then tell others what I did. This is helpful and can quickly render me valuable and even indispensable, but it ultimately plants seeds of self-doubt in those around me. I also feel that my suggestions and criticisms are given undue weight in everyday life by virtue of my intelligence; that I am assumed to be right even when there is no obvious reason that I should be. I wonder if there might be a way – if I were to operate from a greater sense of security within myself – that I might be able to use my intelligence in a way that is empowering rather than disempowering to others.

Returning to a discussion of intelligence as an axis of oppression in general, an emphasis on knowledge and intelligence creates the illusion of a meritocratic society – anyone who passes the test can succeed – while tacitly acknowledging that this sort of learning is readily fostered among the comfortable classes but not lower on the economic ladder. So in reality, these knowledge- and intelligence-based hurdles and incentives impose another mechanism to perpetuate the class divide, while also devaluing those whose natural intelligences are not in the mathematical or analytical arenas.

Origin

Origin – which I will define as whether a person is native or new to a community – is distinct from the previous five axes of oppression. It is unique in that oppression can flow either way, depending on which group has more power. I want to discuss it here, however, because it is also excluded from the framework of mainstream social justice, with origin-based oppressions typically simplified as identity-based oppressions.

We live in a world of human migrations, which are likely to increase in the decades ahead as climate change renders some regions less habitable. People move fleeing oppression and violence, seeking opportunity, or for a hundred other reasons. When enough new people enter a community that social dynamics or economic realities begin to change, a predictable and understandable resentment arises in the native people of that community, the ones that were born and raised there.

We give this dynamic different names, depending on which group has more power. When the new (usually white) people have more power and the existing people (usually of color) are devalued or displaced, we call the process gentrification and the resistance community preservation. When the new people are refugees or economic migrants (usually people of color) and the existing people are white (and usually lower-class, but with more power), we call the process immigration and the resistance racism. When there is no clear power differential, the resentment and divide usually goes unnamed. I moved to my current area twelve years ago, a place where in-migration (of mostly comfortable-class white people, into a mostly-white community) has resulted in significant population growth and increases in housing costs. Even now, I find that very few of my friends were born and raised here, and that there is a real resentment-based barrier to friendship between natives and newcomers.

This is another area in which neoliberal social justice is guilty of oversimplifying oppression to fit into an identity framework. In the past 20 years, the rural area where I grew up has seen a significant influx of Latinx immigrants and Somali refugees. This is a region that has been declining economically for decades, thanks to industrialization of agriculture shrinking the number of jobs overall while simultaneously creating a large number of employment opportunities in the lowest-respectability, lowest-pay range (meat processing, industrial-scale animal production and beet sugar production). The immigrants and refugees have taken these jobs and have begun to revitalize the town centers, opening Mexican and Somali restaurants, clothing stores, and gathering places.

Understandably, many of the residents of my hometown are not happy about these demographic changes. When they express their feelings, mainstream social justice tends to label them as racists. And it’s true that if we define racism as any bias by white people against people of color, then it fits the definition. That said, to really understand whether these people are racially biased or just expressing nativist resentment, we need to ask ourselves if they would feel differently if the newcomers were French (with a language barrier), or even white New Yorkers. Knowing my old friends and neighbors, I suspect they would find such an influx equally troubling.

I’m not suggesting that racist attitudes don’t exist in my hometown, or that oppressions experienced by immigrant communities should be more bearable if they have nativist rather than racist origins. I am simply making a plea for empathy, clarity, and open communication. If someone is grieving change in their community due to immigration, it is not helpful to label them as racist. It is important to understand that human migration will nearly always lead to resentment of newcomers by those native to the area, and that this can be its own axis of oppression independent of the identities of those involved. We will need to work through this conflict many times as migration increases in the years ahead.

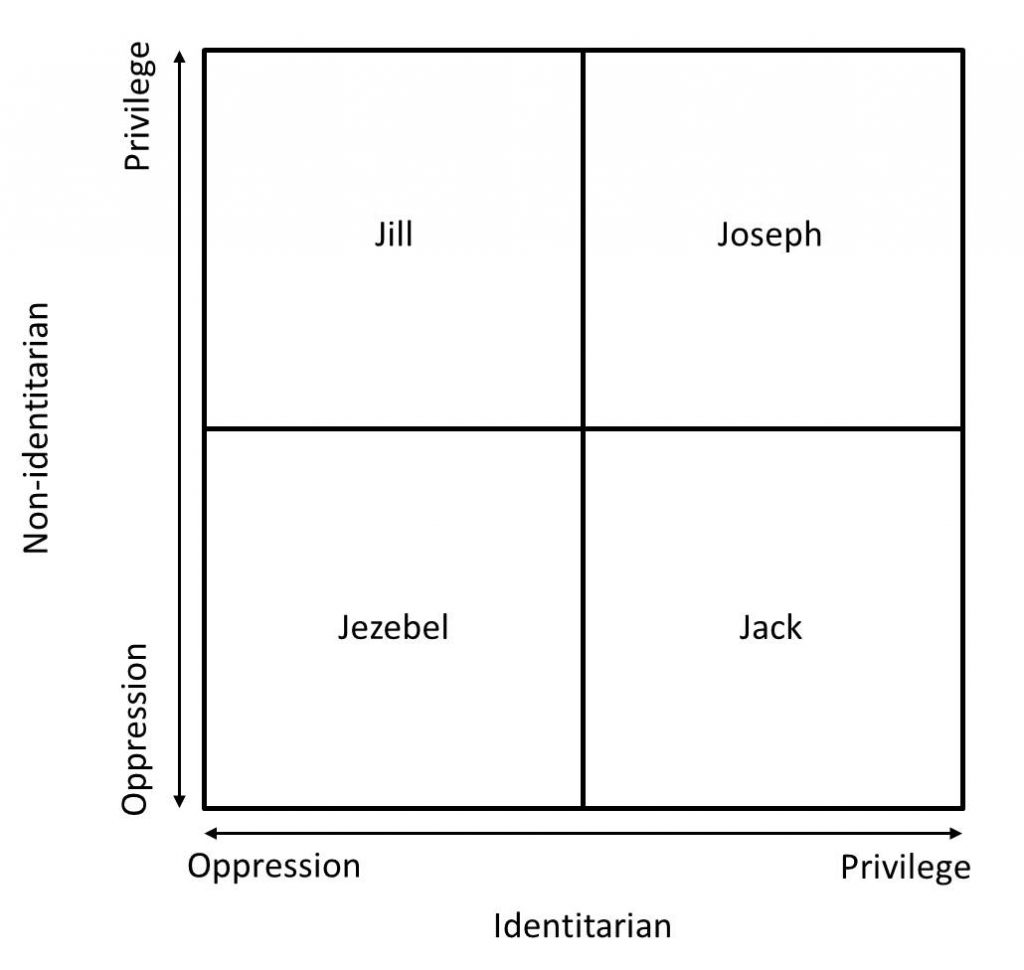

Joseph, Jack, Jill, and Jezebel: Examining the effects of social justice and neoliberal economics along axes of oppression

This can all seem incredibly complex; if we examine occupation, education, status, class, intelligence, and origin in addition to the identities of traditional social justice, we all have our place in a 13-dimensional landscape of privilege and oppression.

For the purposes of understanding exactly how an incomplete framework of social justice is gaslighting America, let’s condense some of these axes and consider four hypothetical people.

Joseph is a straight cisgender white male investment banker, born into a wealthy well-known family and still living in his hometown. He is widely regarded as brilliant and holds a Ph.D. in economic theory from an Ivy League school.

Jack is a straight cisgender white male grocery worker who earns minimum wage restocking shelves on the night shift. He was born into a downwardly-mobile working-class family, where paying rent and putting food on the table left no money for college and a bad taste for debt. He left town to find work in the city, where he is currently living out of his car and hopes to someday be able to afford an apartment with roommates or maybe even a spot in a trailer park.

Jill is a queer transgender woman of color who is a tenured professor at a small liberal-arts college near her home city. Her grandparents immigrated to America and worked their way up to the comfortable classes (that was still possible in their generation), and her family is proud that she has been able to overcome the odds, even if they feel conflicted about her unconventional identities. She was awarded a prestigious scholarship to earn her Ph.D., is the author of several well-read books, and is often interviewed as a success story in the movement for social justice.

Jezebel is a queer transgender woman of color who is currently living with five roommates in a run-down apartment in a big city. She grew up on the wrong side of the tracks, with no money for college and no time to devote to school. Her parents supported her identity but lamented that it would make her already-bleak prospects even bleaker. She left home at 18 seeking an accepting community, and while she has found good people she has not be able to find a stable job that pays anything approaching a living wage given the astronomical cost of housing. She has been homeless several times, has occasionally resorted to sex work to make ends meet, and has contemplated suicide in particularly hopeless moments.

Let’s assume that all of these people are 30-40 years old, and let’s look at how the world has changed since their birth.

Joseph’s life has always been good. He knew from boyhood that he was destined for success, and he just had to play his aces right – with his family’s sound advice – to maintain his position at the top of all of society’s axes of oppression. In the last decades he has noticed that more of his colleagues are women and people of color, which makes for more interesting boardroom discussions but is no threat to his place in the world, which he feels that he has rightfully earned through hard work and family success. He plans to retire young, maybe buy a yacht, and spend more time exploring all of the places he has visited on business trips.

Jack’s life has been a story of diminishing expectations. When he was born, his father earned respect and good wages working at a factory, his family had a mortgage on a modest home, and they hoped to save enough to send their kids to college – or for their kids to build a good life working in the factory. But the factory closed when Jack was about 10. Factories were closing across town and all over the state, as companies moved manufacturing overseas in pursuit of cheaper labor. They lost the house and moved to a small apartment, and Jack’s dad took up drinking. Eventually his mom found work at the local gas station and his dad earned some money as a freelance mechanic, and the family survived, but the dreams of a college fund were gone, and the feeling of being respected for a good day’s labor was gone along with it.

Jack watched with some envy as his classmates, the children of the town’s teachers and lawyers and dentists, took their SATs and submitted their college applications, but at the same time he noticed how little they respected him. Why should he try to play their game when he had already been branded a loser? So he stuck it out, graduated high school, drank beer with his buddies on the weekends, bought an old beater car that he could sleep in if necessary, and took off in search of work. And there he has been stuck for the last ten years, living out of his car, traveling city to city, occasionally renting an apartment, living paycheck to paycheck. Whenever he has gotten close to saving enough to afford a down payment or to go back to school, some major expense – a new engine in his car, a root canal, an emergency surgery – has wiped it away. He dreams small now, hopes to maybe meet someone, find a spot in a trailer park, raise a child or two, probably never retire. He reads about how social justice is supposedly creating a more equal, more prosperous America, but it seems like so much smoke and mirrors, and it has never done a lick of good for him or his family.

Jill’s life has been one of expanding possibility, but not without struggle. Her immigrant grandparents lived the American Dream during that era when hard physical labor paid real financial dividends, and her parents worked respectable jobs in accounting and hotel administration that kept the family afloat and paid for their kids’ college tuition. She struggled with her queer and trans identities as a child – they were seen as shameful in her community – and was ostracized and bullied by her classmates. She avoided some parts of town where white people shouted rude things and occasionally more ominous threats. In college, though, she discovered people like herself and a whole movement to empower people of color and normalize queer and trans identities, and she finally felt welcome.

Jill really found her voice as an advocate for queer and trans communities, and felt like a trailblazer. She rejoiced when queer people were allowed to marry, held a lively celebration with her longtime partner, and they bought a house together and adopted two children. She felt lucky to find a tenure-track professorship shortly after earning her Ph.D., and her ability to translate science to a popular audience made her a minor celebrity in academic circles. While she knows there remains work to be done – she still faces insults and threats in some parts of town – she looks forward to sending her kids off to college and to a long retirement filled with volunteering and world travels.

Jezebel’s life has always been hard, staying alive, day-by-day. She grew up in one of those ghettos that the freeways cut in half, that the white people liked to pretend didn’t exist. She was the oldest of five. Her parents worked the sorts of service jobs where you talked to people all day long and they talked at you, talked through you, yelled at you, blamed you for things that weren’t your fault, demanded you fix their silly little problems. No one paid them any respect whatsoever, so they weren’t above stealing a few items from time to time. Her dad went to prison when she was 16 for shoplifting; he wanted to buy her a dress for her birthday but couldn’t afford it. The cops found a little weed in his car, threw the book at him. A white man probably would have gotten off with a warning. Whatever. No one ever cared about them.

She dropped out of high school then to care for her younger siblings. She felt safer at home anyway, and food stamps and a welfare check complemented her mom’s meager income and kept them fed and housed – just barely. She left home when she could, bought a one-way bus ticket to the nearest big city. There she found other survivors, castaways, beautiful broken unloved young people of all races and identities, but quite a few like herself. They were her family. They survived together, loved together, hurt each other, acted out their repressed pain and trauma together, blissed out on drugs together. Sometimes they broke the law, sometimes they found a place to live, sometimes they lived on the street. Sometimes her friends didn’t survive. Suicide, overdose, homicide. She grieved them all, but no one seemed to care.

Jezebel heard about “social justice” on the news, about trans “liberation,” about gender confirmation surgery, bathroom equality. As if she could afford surgery. As if that were even in her top ten priorities. A home would be nice. A job that paid enough to afford it. People who looked her in the eye and said “thank you” instead of looking through her as though she didn’t exist and telling her she wasn’t working fast enough, smiling enough, telling every customer about the new credit card the company had to offer. Maybe, she hoped, social justice would get around to caring about people like her. But hope was a dangerous thing to feel, it always led to disappointment. Better to just survive one more day.

How Neoliberal Social Justice is Gaslighting America

This, then, is reality as I see it. It is viewed through my lens, of course, but I encourage each of you to re-examine reality for yourselves, to remove the filters that the media and politics may have given you.

Social justice ideology is gaslighting America not by being wrong, but by being incomplete, by ignoring some of the most significant oppressions occurring all around us, every day.

The Josephs of the world, the ones with the most privilege, are not threatened by social justice activism, even as white privilege and male privilege are deconstructed. Their power lies in their status, in their occupation, in their class, and social justice as currently envisioned is no threat to that power.

The Jills of the world, the ones at the top of the invisible (nonidentitarian) privilege ladder and the bottom of the identity-based privilege ladder, have seen real improvement in quality of life due to the work of social justice, and they have also been privileged by neoliberal economics.

The Jacks of the world, the ones at the bottom of the invisible privilege ladder and at the top of the identity-based privilege ladder, have seen a marked decline in quality of life due to neoliberal devaluation of the working class. Social justice activism has done nothing for them, deeming them to be fully privileged.

The Jezebels of the world, the ones with the least privilege along all axes of oppression, have not really been helped by social justice. In effect, the decreasing oppression along identity-based axes and increasing oppression along non-identitarian axes cancel each other out, with the result that the Jezebels of the world remain in a precarious state of societal disrespect and daily survival.

A Plea for the Expansion of Social Justice

It is high time that we expand our conception of social justice to include all axes of oppression.

If you don’t care about Jack, do it for Jezebel, the one who you claim to care about but who you have not helped, because you have not dared to challenge neoliberalism and the unearned privilege that it provides to you.

If we do not expand our conception of social justice, it is likely to be defeated, and a great deal of good work will be lost. I mean this quite seriously. The Jacks of America are Trump’s base, and they are chomping at the bit to spite “social justice warriors”, who they (quite rightly, it would seem) see as blaming the Jacks of the world for identity-based oppressions while remaining blind to the neoliberal destruction of the working class. They are not a majority, but a less divisive populist voice than Trump could unite the Jacks and the Jezebels against neoliberalism, and if social justice remains tethered to neoliberal ideology then out it will go, the baby out with the bathwater.

Furthermore, it is ethically inconsistent, i.e. hypocritical, to privilege some forms of oppression over others. I cannot think of any argument to support it that does not boil down to “but I like my privilege, and those people don’t deserve it.”

There should be no those people. We are all people. We all deserve love, respect, support, basic human rights, a living wage. Is that too much to ask?

We need to focus on respect in place in addition to providing opportunities for advancement. Equity in this context is not just about providing scholarships and grants so that children of truck drivers and farm workers can go to college and join the comfortable classes. That only results in a few “success stories” in the media while some new oppressed group of “not-really-people” – refugees, undocumented immigrants, downwardly mobile manufacturing workers – takes those jobs because they have no better options. We need truck drivers, farm workers, and cashiers every bit as much if not more than we need lawyers, professors, and administrators. So we need to respect the people who perform that labor, pay a living wage, offer benefits, pay enough to compensate for the dangers of the job. People should be able to choose their path in life, not be forced to compete in a rigged casino and ultimately take what they can get. This means that some of the jobs with the toughest conditions or the highest likelihood of injury might need to pay several times their current wages.

The modern institution of higher education has created a gated community around the “good” jobs – the ones that generally pay well, provide health and retirement benefits, require less physical risk and discomfort, and confer societal respect. College is the gate, and the guards are the admissions committees, the administrators that set tuition rates, the student loan officers, the standardized tests that together decide which humans are worthy and which humans are not. It is high time that we break down this barrier. If we can accomplish that through free college for all or a relaxation of degree requirements – or both – it will be a victory for equality.

So…do the work to stomp out racism and misogyny within yourself, but also:

- Stand up for a living wage for all work.

- Stand up for universal health care as a human right.

- Stand up for affordable housing. And not just a restriction on rent increases but rent reductions. You know, actually affordable housing for people earning minimum wage, to allow them to save money and move up in the world.

- Respect everyone you meet. Cashiers and fast food workers included. Look them in the eye. Thank them. Do not judge them. Do not pity them. Do not blame them for mistakes that they make. How many mistakes would you make if you did that work all day?

- If you’re a member of the comfortable classes, cultivate friendships with people in the working classes, if possible. They will expect you to be condescending, and you might come across that way without intending to. Ask them what they need to improve their lives, and then use your privilege to help make it happen.

- Be willing to pay what it costs for people to earn a living wage. Yes, that means food and clothing will cost more. If you’re a member of the comfortable classes, you can afford it.

- Be kind to homeless people, and support efforts to provide them with jobs, housing, and adequate mental health care when needed. Don’t stigmatize them or try to NIMBY them out of your neighborhood.

- Be willing to accept enough. Enough money, a big enough house, enough stuff, enough travel. You don’t really need more, and other people need some too.

Can we do this? Together?

8 Responses to Invisible Axes of Oppression: How Neoliberal Social Justice is Gaslighting America